Surrealism – perhaps the most prominent, and certainly the longest surviving of the 20th century’s innumerable avant-garde episodes – was a movement that encompassed so many forms of media that it became not a style of art but, ultimately, a state of mind. It was, after all, precisely ‘states of mind’ that Surrealist artists were concerned with, rejecting reason, logic, and rational thought and ruminating instead on the mysterious truths locked within the confines of human unconsciousness.

Coined as a term by Apollinaire in 1917 and ‘baptised’ by André Breton in his manifesto of 1924, Surrealism began life not in exhibitions or on gallery walls but in the written word. By the early 1930s, alongside theatre and poetry, it had embraced painting, sculpture, film, photography, fashion, psychology, philosophy, linguistics, political activism and pseudo-scientific study.

Salvador Dalí - 'Nude with Veils'

Salvador Dalí - 'Nude with Veils'

Though the term was retroactively applied to a number of ‘proto-Surrealist’ artists, from de Chirico right back to Hieronymus Bosch, Surrealism proper was born on the crest of a post-war Dada swell; for a time, the two movements coexisted, as Breton wrote, ‘like two waves overtaking one another in turn.’ An anti-authoritarian protest that fed off public unease at the butchery on the front, Dadaism emerged spontaneously amid wartime unrest in Zürich, Cologne, and New York.

Its proponents denounced ideas of order and hierarchy in all spheres of life, from aesthetics to politics, seeking to rid the world of arbitrary categorisations. Their art – or rather, their anti-art – laid waste to traditional notions of craft. It was typified by collative media such as collage and the ‘readymade’, found objects thrust into gallery spaces to challenge the idea of art as the product of deliberate practice. Works like Max Ernst’s early cartoons or Duchamp’s notorious Fountain looked to shock, mock, ridicule and frustrate the very audience from which they derived their definitions as ‘artworks’.

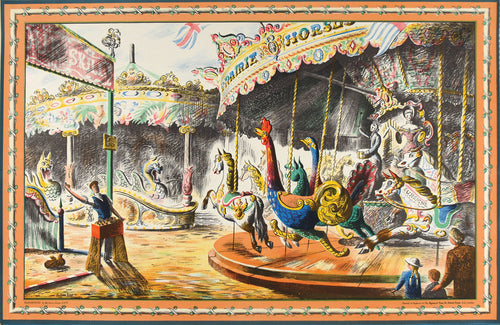

Max Ernst - lithograph from the late suite 'La Ballade du Soldat', incorporating elements of collage

Max Ernst - lithograph from the late suite 'La Ballade du Soldat', incorporating elements of collage

Dada’s insistence on disorder, its refutation of conventional reasoning, and its fetishisation of the unexpected were all themes Breton admired and sought to adapt in the launch of his Surrealist movement. When, with the help of fellow author Philippe Soupault, Breton published his Manifeste du surréalisme in 1924, however, his text marked a definite departure from the anti-establishment outbursts of Dada. It also contained the first official definition of Surrealism as, ‘pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express…the real functioning of thought, in the absence of any control by reason, exempt from aesthetic or moral preoccupation.

Breton was a keen student of Freud, and had employed his practices of free association as a wartime psychiatric nurse attending sufferers of shell shock. Extrapolating from Freudian psycho-sexual analysis, Breton determined that the real source of one’s creative powers lay in the subconscious, in the realm of dreams and suppressed desires, wherein one would find uninhibited images of sur-reality – of truth beyond reality.

Dalí - Untitled Lithograph

Dalí - Untitled Lithograph

Unlike the Dada movement, which by its very nature had renounced the idea of exclusive membership, Surrealism was a collective that contributors could join and from which they could be expelled, sometimes by committee, more often on Breton’s whim, who acted as chairman of its Parisian base. Though the first iteration of Breton’s manifesto had made little mention of the visual arts, he soon looked to identify Surrealist sympathies in other creative fields. In 1925 he published an essay on Surrealism and Painting, introducing the idea of visual ‘marvels’ - images of truth revealed in one’s subconscious - and within a year had opened the first ‘Galerie surréaliste’.

Throughout the late 1920s, numerous artists became closely associated with Breton’s new movement. Some, such as Miró, were adopted Surrealists by name yet eventually looked to distance themselves from the term; others, such asDalí, whom Miró first introduced to the group, would become its most prominent members. Magritte, famously, was reluctant to join, despite his associations with the Belgian branch, while artists like André Masson actively fought against Breton’s vision as the Surrealists began to divide and form independent factions.

André Masson - 'Hommage à Dorothea Tanning'

André Masson - 'Hommage à Dorothea Tanning'

Unlike Impressionism or Cubism, there was no definitive Surrealist mode of expression. Surrealism was ‘not a style’, wrote the playwright Antonin Artaud, but ‘the cry of a mind turning back on itself.’ For artists, however, Breton’s stress on automatism as the defining Surrealist creative act posed significant problems. Painting, with all its concomitant apparatus, did not lend itself to the immediacy of automatic creation, forcing artists to think along new avenues of expression.

For some, like André Masson, this involved turning to drawing, where the freedom of ink or pencil subconsciously scrawled with the hand mimicked the Surrealists’ earlier experiments in automatic writing. Others imagined new approaches to the canvas that incorporated chance or devolved creative power from the hand to the material: Ernst’s techniques of frottage and grattage involved placing textured objects underneath canvas or paper and rubbing with pencil or scraping through paint to reveal an imprint of the surface beneath.

a composition by Ernst using just the rubbed textures of 'frottage'

a composition by Ernst using just the rubbed textures of 'frottage'

On the other side of the movement were those who sought to convey Surreal automatism not through medium or process, but purely through subject. For artists like Dalí and Magritte, the world of dreamscapes and of half-asleep hallucinations offered a rich vocabulary of images to explore. Their paintings incorporated vast landscapes of infinite distances, a visual representation of the boundless space of the untapped unconscious mind.

two lithographs from Magritte's 'Les Enfants Trouvés' suite

two lithographs from Magritte's 'Les Enfants Trouvés' suite

Strewn throughout these desert-like wildernesses, objects and figures cast inexplicably long shadows, architectural structures defy the laws of physics, and entities seem to metamorphose into one another or melt into the very fabric of the painting itself. Their super-realistic style of depiction neutered any expression of painterly strokes, reinforcing the sense that the dream world represented a more truthful – and beautiful - reality than the world observed by the waking eye.

Félix Labisse - 'Aube' ('Dawn')

Félix Labisse - 'Aube' ('Dawn')

Repression lies at the heart of almost all Surrealist art: repressed sexual desires, violent urges, fantasies and fetishes, and suppressed memory. Its members were encouraged to ignore their inhibitions, to bypass the restrictive clutches of the conscious mind through psychoactive substances, alcohol, forced lack of sleep, and orgiastic sexual displays and to unleash as much of this subconscious world in their art.

Dalí - Untitled engraving from the 'Les Amours de Cassandre' suite

Dalí - Untitled engraving from the 'Les Amours de Cassandre' suite

Deep-seated erotic fixations and perversions were of particular interest to artists like Hans Bellmer, explored through the recurring theme of the sexualised naked female figure and marionettes, bizarre puppets in which nude figures, most often those of women, were transformed into aberrant clusters of phallic and vulval divisions.

Hans Bellmer - engraving from the 'Marionettes' suite

Hans Bellmer - engraving from the 'Marionettes' suite

Other behaviours deemed transgressive by the contemporary viewing public – homosexuality, cross-dressing, sadomasochism, and violent sex – were openly examined through explicit photography and film, from the torsos of Man Ray to the doubly-exposed experiments of Maurice Tabard.

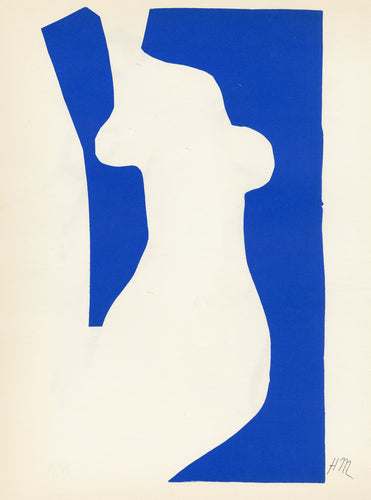

Paul Wunderlich - 'Torso sur une Pierre Bleue'

Paul Wunderlich - 'Torso sur une Pierre Bleue'

In its willingness to analyse even the deepest and darkest recesses of the human brain, to indulge in its strangest flights of fancy, the Surrealist mood infected almost every creative and academic corner of life. It was perhaps the only art movement to have its own department of research, the Surrealist bureau, set up by Breton to conduct voluntary surveys of people’s dreams and to contribute towards a greater picture of what exactly Surrealism meant to society at large, not just its inner intellectual circle.

Dalí - 'The Agony of Love'

Dalí - 'The Agony of Love'

This scope of vision, in which Breton had sought not merely an art movement but a fundamentally radical way of viewing the world, saw Surrealist practices continued well beyond his death in 1966 right up to the present era. Its artists’ works have influenced graphic design and advertising; its revolutionary ideas of automatic creation fed into the explosive paintings of American Abstract Expressionism; and its extraordinary infiltration into modern cinema can still be felt to this day. Few rival movements of the time could lay claim to so pervasive an influence, nor to have permeated so deeply the public consciousness.