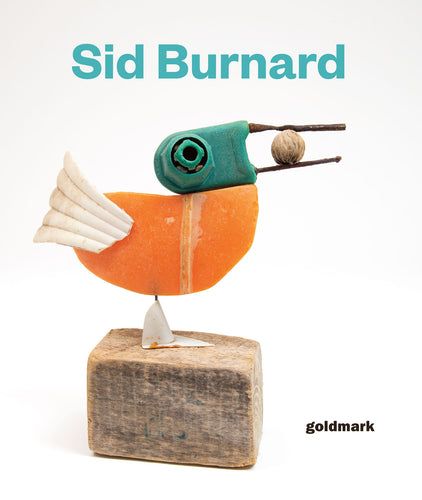

The menagerie of characters in Sid Burnard’s ‘Curious Kingdom’, to use his choice of phrase, immediately puts you at ease. I dare you to look at O.A.P. or Jaws Truly and not even crack some semblance of a smile. Their playful postures and personalities are all characterised with such entertaining names, from Fiddler on the Roof to Fowl Play and the tongue-in-cheekPole Dancer. A conversation with Sid is much the same as engaging with his work; you can’t help but smile.

Pole Dancer

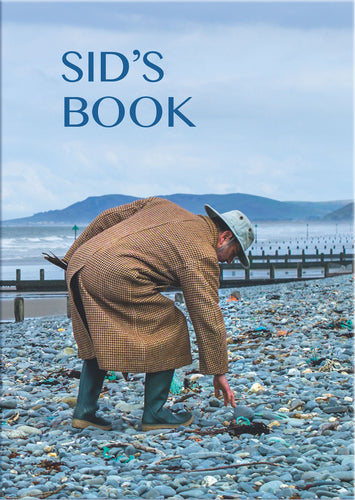

I’d been charged with interviewing this assembler of birds and beasts for our upcoming Winter magazine. Before chatting with Sid, I spent some time reading his published diaries and watching Goldmark’s feature film to get a sense of the man behind the work (I recommend you do the same). Two things struck me. First, the particular way that he talks about his creatures. He isn’t simply making a bird by combining two pieces of wood; he’s committing a head to a body. None of the pieces that make up Sid’s various constructions are altered: they remain as found from one of his many days spent beachcombing along the west-Wales coast. Pieces of driftwood and all manner of manmade objects are to Sid exceedingly valuable: ‘It is my treasure, my currency and it’s precious.’ Sid introduces pieces to each other, as if they are long-lost friends. They ‘meet’, become a part of a greater whole and live out the rest of their days together. What began often as litter is transformed, all thanks to his wonderful imagination.

Yet, these creations are produced by a man who gives the sea more credit for his ingenious work than he does himself. Sid’s humility was palpable before our conversation even began. When asked if he views himself as an artist he replied: ‘I see myself as an interpreter of found objects. The true artists are the elements: sea, wind and sun…I certainly have a great sense of wonder at the natural world. I’m a celebrator who likes to share.’ Upon learning the lengths that he often goes to in creating his pieces, one wonders if perhaps he is underselling himself…

O.A.P.

At some point during the beginning of our conversation I remark how his creations are ‘so full of humour, and so easily achieved’. As soon as the phrase left my mouth I realised that ‘easy’ was entirely the wrong choice of word. Sid has beach-combed his entire life; it is something he determines is deeply rooted in his DNA. It seems idyllic, walking along the coast with his family, collecting his ‘treasure’ of driftwood and abandoned junk. But Sid beach-combs whatever the weather, lugging heavy pieces of freshly landed driftwood over considerable distances.

Aztec Bird God

As he points out, ‘windswept, rain-lashed beaches are not for the faint-hearted.’ Not one to take himself too seriously, he jokes that it’s a good thing he is short in stature: he doesn’t have so far to fall when carrying his prizes. At 69 his energy and enthusiasm for his work is clearly unwavering: ‘As long as I can bend down to pick things up then I can keep going.’

Fowl Play

The assembling of creatures that follows is by no means an easier task. This is perhaps due to the pressure that Sid puts himself under. He currently has a collection of at least two thousand beach-combed items and ‘each and every one is not just rare, it is unique.’ He believes he ‘owes it to each item, organic or man-made, to bring his imagination and very best efforts to interpreting them.’ Thus, he remains slow to use his material, ensuring it is used to the very best of his ability.

Conscious not to ruin any of his treasure he uses only a hefty drill and iron rods in order to construct his imaginings. There is no second chance: drilling a hole in slightly the wrong position can completely change how one piece balances on another, thus throwing off the whole composition. This isn’t a precise art, and Sid does it all by eye, estimating to the best of his ability; then, as he declares, it is a matter of sheer hope, a leap of faith. He laughs, and explains that he always says ‘when people buy a piece of mine they’re buying a little bit of my pain too!’ When asked if it had become any easier over time he answers ‘if anything it’s harder.’ He likes to challenge himself, push himself further because it is ultimately more rewarding. I couldn’t have been more wrong when I suggested his efforts were ‘easily achieved.’

Comb Over

Despite the intensity with which he works, fun and a sense of humour are essential. With nature as his inspiration his imagination knows no bounds because, as he points out, ‘no matter how extreme or far-fetched a creature emerging from my ‘Curious Kingdom’ might appear, nature will have conceived a far more outrageous character’. He never sets out with a particular character in mind, rather ‘the material leads me’: ‘I'm a great observer of people and animals. Situations can be pure theatre. Postures, stances, gesticulations, faces and emotions reveal so much. These natural performances have been subconsciously stored up in my memory, ready to surface into compositions.’

Take for example, the Yellow Booted Dumbstruck, a bird that came into being thanks to all three members of the Burnard family - a team effort. Each piece, from ridiculous plastic rake feet to protuberant wire-cutter beak, has contributed to creating a whimsical whole, so aptly named, as only Sid can, that all you can do is grin. If he can make people smile, he says, then he is satisfied.

Old Forest Birds

The very personal nature of Sid’s work means that, ‘Every piece that leaves is missed. They include a part of me. Some take my breath away. If I meet them at a later date, I always smile; recall where or when we first met, and how exhausting and difficult it was to join the parts. And they seem to thank me for finding them a new home.’

Sid has some 50 new pieces ready to be rehomed, all of which will surely be a product of his care, humour and attention. His skill makes disparate pieces appear as if they were destined to be together, so much so that it may seem effortless. But, whenever you are looking at a creature from Sid Burnard’s ‘Curious Kingdom’ remember that they are no accident: they exist because of their maker and his extraordinary commitment to his craft.