Modernist, soldier, dreamer: David Jones was all these and more, one of few artists of whom we could truthfully use the word ‘unique’. With a recent Pallant House exhibition and a major new publication on his life’s work serially broadcasted on BBC Radio 4, this indefinable artist is of sudden, resurgent interest.

portrait of the artist

portrait of the artist

Born in 1895 in south London, Jones’ considerable early talents meant that he was allowed to leave school to begin studying at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts when he was just 14 – too young, in fact, to attend the college life drawing classes. With the outbreak of the First World War he enlisted as a private in the Royal Welch Fusiliers in 1915, fighting in the trenches for a full three years.

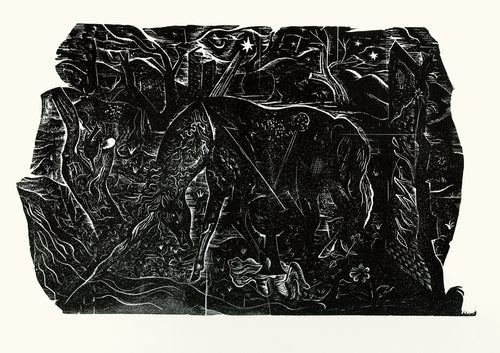

'Everyman', wood engraving

'Everyman', wood engraving

In 1916 Jones was shot during the Battle of the Somme and invalided in 1918. Though it provided the basis for his first prose-poem In Parenthesis, later celebrated by Eliot and Auden as a modern-day masterpiece, Jones’ involvement in the carnage at Mametz Wood haunted him for the rest of his life. He suffered trauma irregularly in the form of neurosis, and his first-hand experience of conflict – retold in his work through the shifting lens of violence, compassion, communion, and Christian sacrifice – bled through to his day-to-day living: visiting Jones in the 1950s, the composer Igor Stravinsky recalled a simple bedsit, possessions kept close to the mattress in military order, and the artist himself, a holy man in his cell, still living as if confined to a wartime bunk.

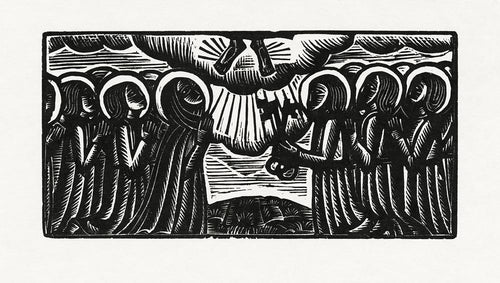

'The Crucifixion', wood engraving

'The Crucifixion', wood engraving

It was also during the war that the seeds of Jones’ spirituality were first sewn. Sent out to look for firewood in the woodlands surrounding Ypres, he stumbled upon an impromptu mass held in a ramshackle farmhouse. Something of the ritual, with its two points of flickering candlelight, white altar cloths and a few huddled figures in khaki, struck an accord: a moment of serenity in three years of madness. It was not long after returning to England, studying briefly at the Westminster School under the tutelage of Walter Sickert, that he converted to Roman Catholicism and left the London smog to work under the renowned engraver and stone carver Eric Gill.

three panels from 'A Child's Rosary': 'The Nativity' (top), 'The Carrying of the Cross' (middle), and 'The Resurrection' (bottom)

three panels from 'A Child's Rosary': 'The Nativity' (top), 'The Carrying of the Cross' (middle), and 'The Resurrection' (bottom)

Jones first joined Gill and his community at Ditchling in 1921, becoming a member of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic. The commune aimed to combine domestic life, the labours of arts and crafts, and spiritual faith in a single location, a garden of paradise established in reaction to the industrial slaughter and the mechanization of man that the recent war had come to represent. While Jones’ style remained thoroughly his own – lyrical, loose, always softer in touch - Gill offered guidance on the techniques of engraving in wood and copper that proved instrumental in the more conceptually advanced prints of his later years.

'The Waters Compassed Me About', wood engraving

'The Waters Compassed Me About', wood engraving

When Gill left Ditchling for the Welsh village of Capel-y-ffin in 1924, Jones followed him, continually refining his engraving methods and developing an ever clearer artistic vision. Religious imagery became the major recurring theme of his work: his men, be they soldiers, sailors, or Arthurian heroes, took on the alternately pained and pious image of Christ; his women, the saintly aura of the Madonna and the sexual ecstasy of St Theresa.

'St. Dominic Blessing a Friar', wood engraving

'St. Dominic Blessing a Friar', wood engraving

He excelled in the methods of wood and copper engravings, investing them with the lilting quality of line that characterised his drawings. Typified by mystical and Biblical imagery, his work amalgamated sacred and mythological symbols with scenes of imagined fantasy. Under Gill, he also learnt the crafts of typography and lettering. While to his tutor the written word was like sculpture – clean-cut, with the coolness of stone monument or epitaph – in Jones’ hand it became visual poetry, tender and romantic, flowing over and around the page and spilling freely from its lines.

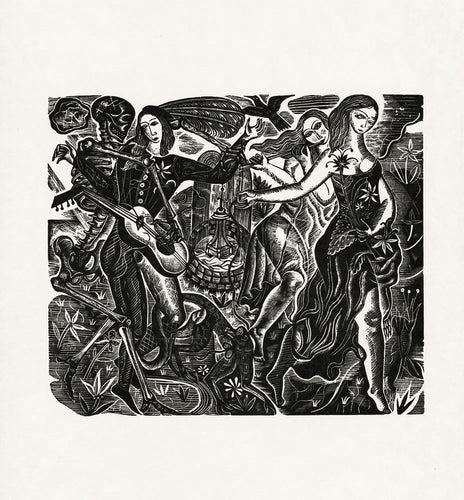

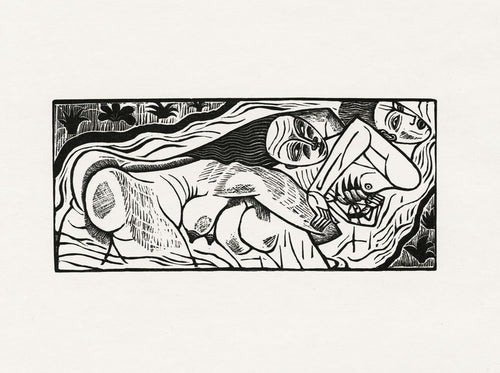

(above) 'Apparitions (Socrates et al.)'; (below) 'Female Yahoo Embraces Gulliver'

(above) 'Apparitions (Socrates et al.)'; (below) 'Female Yahoo Embraces Gulliver'

For a time he was engaged to one of Gill’s daughters, Petra. Introverted, shy, wholly devoted to his work and still suffering acutely from his trauma, Jones must have always seemed an incompatible match with the comparatively vivacious Petra, whose striking, willowy features inspired many of the female figures in Jones’ prints. Whether he knew of her 'indecent' liaisons with her father, and whether those liaisons continued secretly throughout their engagement, cannot be known for sure; but by 1927 the relationship was over, and Jones would never later marry.

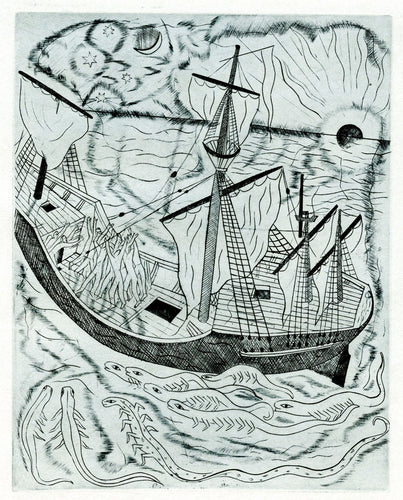

'The Curse', copper engraving from 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'

'The Curse', copper engraving from 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'

In a catalogue that defies categorisation – he drew and painted like a craftsman, cut like a poet, wrote like a visionary – best celebrated are his copper engraved illustrations for the 1929 edition of Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Hampered by a swiftly failing eyesight, these prints would be the last he ever produced, dedicating the rest of his artistic career to luminous watercolours, oils, and the tentative, delicate draughtsmanship that had underpinned his graphic output.

preparatory pencil sketch for an unknown engraving; the text below reads 'My love is on an island on an hill'

preparatory pencil sketch for an unknown engraving; the text below reads 'My love is on an island on an hill'

As was to be expected of an artist whose words, both written and designed, were made to dance, he spoke of the drawn line as if it were language: (there is a) lyricism inherent in the clean, furrowed free, fluent engraved line. In the Ancient Mariner engravings he sought not merely to illustrate but to get in copper the general fluctuations of the poem…

'The Wedding Guests', copper engraving

'The Wedding Guests', copper engraving

Jones died in 1974. In the intervening years, he had been appointed CBE, published his last great work, The Anathemata, and been acclaimed by Sir Kenneth Clark as absolutely unique – a remarkable genius; yet he remains, to this day, a still little-known figure. Renewed attention to his output in books and exhibitions should offer hope, for there is a great deal more to be discovered in these beautifully intimate, personal, introspective works of art.