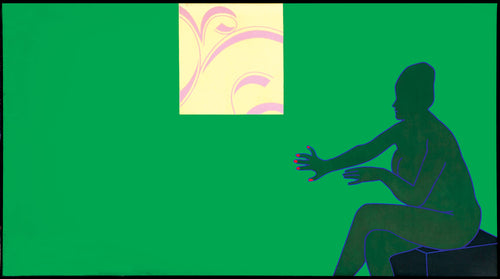

'The Manicurist' (1965/6) - one of the earlier and, at 277 cm wide, larger of Greaves' 'flat' paintings

Greaves had enjoyed instant and widespread critical acclaim in the early 1950s. The landmark solo exhibition at the renowned Beaux Arts Gallery in London, 1953, which brought him substantial recognition in the national press, opened when he was still a student at the Royal College of Art. Greaves, alongside John Bratby, Edward Middleditch and Jack Smith, was labelled one of the ‘Beaux Arts Quartet’: the four poster boys of ‘Kitchen Sink’ painting, celebrated for their muted oils depicting scenes of suburban social realism.

'Fruit on a Table' (1959) - a typical early still life, produced before Greaves' 'reinvention'

Ten years later and his painting had changed almost unrecognisably. Shedding the Kitchen Sink moniker, this new style drew upon early years working as a sign-writer’s apprentice. Relinquishing gestural marks and textures of paint, he began instead to combine the bold outlines and expressive colours of Pop with the melancholia which had served his earlier domestic interiors and still lifes.

'The Sower'

The Sower is typical of this new period, produced after a 1967 holiday in Provence with the photographer David Mindline. Here, in charcoal sketches made in the heady southern French countryside, Greaves invoked the spirit of Van Gogh, for whom the Provençal light and landscape was so important: ‘Every decade or so, I felt I re-understood Van Gogh…It was very odd coming to it through my own work.’

Van Gogh's 'The Sower' (1888) - Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The Sower owes a spiritual and thematic debt to Van Gogh’s many paintings of sowers in fields, and in particular to an 1888 oil of the same title. The thick, impasted golden sun of Van Gogh’s original is transmuted here to a refulgent sphere, brilliant orange offset by a background of purple, its chromatic opposite. The sower himself is reduced to a giant hand, a recurrent visual theme in Greaves’ later paintings, scattering chrome yellow seeds across the breadth of the canvas.

So hot is the sun overhead that its corona overlaps the outflung hand of sower, recolouring his thumb like a great disc of coloured acrylic: ‘[Here] the interval’, he wrote later of such paintings, ‘the intervening space, invaded, and to a certain extent, annexed the objects. Similarly the object pressurised its environment. Edges became crucial. Outline became crucial, ambiguous and then an end in itself. Line emerged as form.’

With hard edge and flat colour, The Sower evidences Greaves at a critical stage in his career: abandoning that which had brought him approbation, dismantling his pictorial language, rebuilding the visual remnants into a body of newly expressive, symbolic work.