Frank Brangwyn was a workhorse. His astounding work ethic, matched by few contemporaries, produced, by conservative estimates, in excess of ten thousand works of art across a multitude of media. He was an artistic chameleon, capable of adapting to new art forms as they were introduced to him, and held a profound belief in art as an occupation, rather than intellectual exercise, in which his own desire to create became all-consuming.

Brangwyn was a true autodidact. He received no academic education in the arts, despite demonstrating an innate talent for drawing from an early age. Though he would encounter a number of important mentors early in his career who helped shape and direct the young artist’s future, what little formal training he received in his youth came initially from his father, William. Brangwyn senior was a specialist in ecclesiastic interiors and textile design with aspirations to become an architect.

Having emigrated to Belgium in 1865, he set up a workshop and embroidery studio around which his son would spend his formative years. The atelier employed a rich and eclectic fusion of styles, from Gothic and Flemish façades to Anglo-Oriental embroidered silk banners, a heady intercultural mix that would inform his son’s later work.

detail from Bridge Builders

In 1874 William brought his family back to London in Shepherd’s Bush, a suburban area thrust into a widespread programme of urbanisation and construction. Early in his own career he had been encouraged to draw churches and chapels from sight to gain a better understanding of their structural workings, and this was a discipline he passed on to his son in turn.

London’s scenes of industrial grime seemed to the young Brangwyn a far cry from the meandering streets of Bruges where he had grown up. He lapped up this new world with excitement, sketching building sites, scaffolded frontages, and sweating labourers at work, all the while building a visual repertoire that he would draw upon in future prints and paintings.

Old Bridge, Rome

Brangwyn’s first major breakthrough as a young artist came when his facility for drawing was discovered by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo and Selwyn Image, the two influential designers who together had established the Century Guild of Artists in 1882. Brangwyn was among the first young men to be affiliated with the group, which employed associated craftsmen and manufacturers in the production of interiors.

Mackmurdo was chiefly an architect, and he impressed on Brangwyn and his colleagues the importance of uniting interior design with architectural setting, advice that would prove essential in Brangwyn’s extraordinary mural commissions for which he became best known.

Ponte Rotto, Rome

Mackmurdo was clearly impressed by Brangwyn, who at just fifteen years old had demonstrated both a prodigious draughtsmanship and a lively enthusiasm for the ‘decorative’ arts. He helped secure for him his second major apprenticeship in the workshops of William Morris, where he was expected to trace and enlarge designs for textiles.

Morris’ company promoted a holistic approach to design, with motifs cohesively repeated and reinterpreted in a number of different media from ceramic tiles to fabrics, carpets, wallpaper and furniture panels. Brangwyn quickly developed the transferable skills required to keep up with the work; economy, industry, and adaptability were qualities that defined much of Brangwyn’s career, and it was here on the workshop floors of Mackmurdo and Morris that they were most visibly developed.

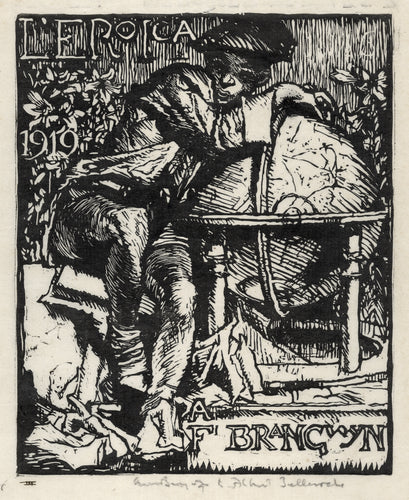

Sketchbook drawing, reproduced by Brangwyn's Japanese colleague Yoshijiro Urushibara in extraordinary woodcut

Practical experience in a studio environment had taught Brangwyn how to work with speed and at volume, but the assignments he was given - scaling and working up designs - were artistically stifling. Before long, he sought to broaden his horizons and spent the next decade on intercontinental sailing expeditions, initially around the British coast, and later as far afield as Venice, Cape Town, the Black Sea, and the coast of North Africa.

Sante Maria della Salute, Venice

Sailors, ships, and Thameside docks had been a mainstay of inspiration while in London; now, as a crew member, he witnessed first-hand his fellow seamen at work, contributing to a number of maritime sketches and his first oil painting to be accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1883, completed when he was just seventeen. His travels provided fresh scenes of Mediterranean and African colour, from Moroccan markets to the old Dutch towns of South Africa and the winding canals of Venice, and he drew and painted ceaselessly.

Freedom of the Seas

At first, Brangwyn’s earnings as an artist were meagre as he reputedly resorted to fuelling his stove with unwanted watercolours and sketches. But by the end of the 19th century his circumstances began to improve substantially. He had by now developed an international reputation as a vibrant and robustly hard-working modern artist, though critics in Britain remained sceptical of his work.

He began to provide countless illustrations for books, and magazines, through which knowledge of his work at home and abroad grew exponentially. An association with Siegfried Bing, owner of the renowned Parisian ‘Galeries l’Art Nouveau’ who had contracted Brangwyn to paint murals for the shopfront exterior, also brought further commissions and a steady source of income.

study for a mural, gridded up for transferring to the larger scale

Through his routine tasks under Morris and Mackmurdo, Brangwyn had learnt to efficiently transfer smaller designs to large surfaces; murals made for a natural transition, and over the next forty years he would complete a staggering twenty commissions that combine to over half an acre of canvas.

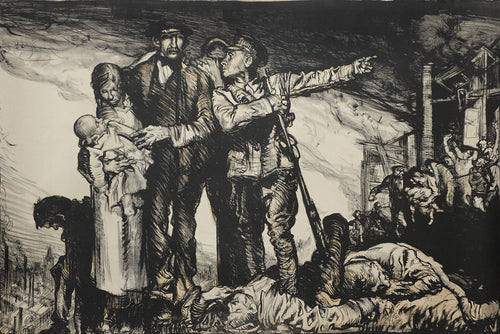

United States Appeal, wartime lithograph

With the outbreak of war in 1914, Brangwyn also turned his hand to designing posters in support of the war effort. Though never officially appointed as a War Artist, his viscerally realistic images of combat at the front remain among the best-known British examples of the period. So popular were they, despite their grim subject matter, that the Kaiser was supposedly prompted to place a bounty on his head.

Blacksmiths

Less well-known but no less extraordinary were his achievements in printmaking, and especially in etching. From the 1920s onwards Brangwyn produced vast numbers of prints, taking large-scale construction projects and architectural views as his primary subjects. Men at work remained a perennial source of interest, their backs bent double, coal-caked shirts tied round waists.

The Building of the Ship, enormous zinc etching

In images like The Building of the Ship, these toiling labourers shrink beside the colossal scale of their structures. Brangwyn’s use of the etching medium reveals a mastery of its techniques: in his enormous views of bridges and cathedrals, many of which measure almost a metre across, the full width of the zinc plate is used to tonal effect.Religious imagery was a common theme too. Many of Brangwyn’s images of large churches or cathedral interiors invoke the feel of pilgrimage, of arriving at a scared destination: views of the immense buildings themselves are obscured by tumultuous crowds of people, or are seen through a sea of masts and tangled rigging.

Notre Dame Cathedral

In later life, as he became increasingly infirm through rheumatism and stomach pains, the religious aspect of his work became more intimate and reflective, as in the tiny but beautifully accomplished etched illustrations for the Book of Job. Brangwyn’s own Catholicism was deeply, though privately, felt: he attended church only irregularly, preferring the miniature chapel he had assembled in an alcove in his home in Ditchling, where he lived from the early 1920s until his death there in 1956.

scarce touched proof from the 'Book of Job' suite of etchings

Public and critical opinion of Brangwyn’s work has always been divided, reflective, perhaps, of the way in which he occupied a no-man’s land between the modernist avant-garde and the academic establishment, neither of which fully embraced his work. His eventual recognition came late in his career: in 1952 he was afforded a major retrospective at the Royal Academy, the first of any living artist in history, and ten years earlier had been knighted for his services to the arts.

Via Dolorosa, No. 1

Yet in the half-century hence his work has been largely ignored, both by artists and commentators. To many, Brangwyn’s colonial-era subject matter and his commercial association with the British Empire have tainted his work as jingoistic and imperial; to his advocates, this is a clichéd response, and one that ignores the colloquial nature of Brangwyn’s work, which exalted the perspectives of working men regardless of colour and creed. What cannot be disputed are his polymathic talents, and the awe-inspiring breadth and depth of the legacy of work he left behind him.