GG:

What can we expect to find in your upcoming show?

Keeler:

Working towards an exhibition is a very strange business, because it implies that you have a vision for this space and that this collection of work is going to convey something quite specific. You've got some reason for having this show that is going to send people away different from the way they came in. What really happens is I go out into my workshop and I make pots, and the pots accumulate in their own special way. I haven't made them to any purpose other than my need to make pots, though I've tried to include a variety of forms, big and small.

I suppose inevitably it is going to reflect me, which is kind of daunting. I haven’t reinvented myself in order to make a cohesive exhibition, so if it's not cohesive it's because I'm not cohesive. I hope above all it reflects my feelings about the business of being a potter, of making things for other people.

GG:

Where do you find inspiration for your work?

Keeler:

New ideas often come from old pots. It can be something very simple, like a little beading that you see. There's a little mug that I should have bought at a fair that still haunts me, made around the 1760s, a very simple cylinder with a rouletted line about a third of the way down from the rim. It was just so perfect, the choice of that pattern and placing it at that level. No doubt the person who made it didn't give it a second thought; they just put it where the proportions said it was supposed to be, but it was wonderful. I've been putting roulette lines around my mugs ever since.

I’m fascinated by that whole period, from the middle of the 18th century on where there were so many ideas around, so many things coming into the country from foreign lands, exotic creatures, exotic fruit, all sorts of wacky objects that were entering people's lives and they were trying to make sense of it all.

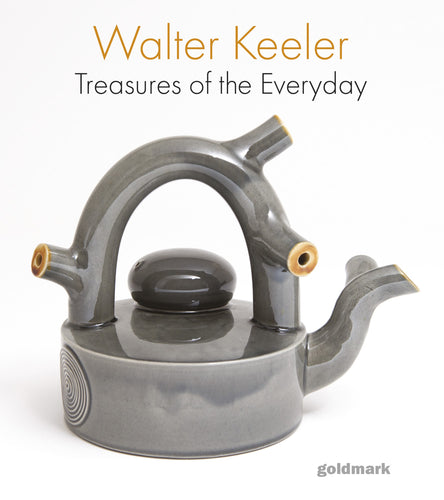

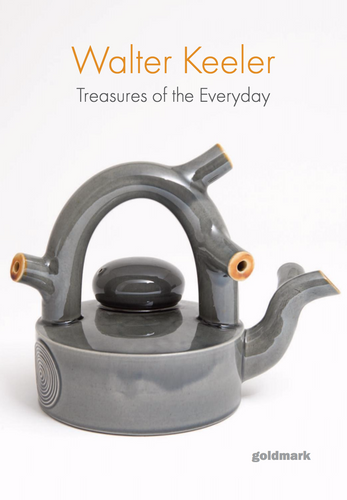

Amongst all this craziness were the crabstocks, which are basically handles, spouts, and other ceramic appendages that are modelled to look like branches of trees with chopped off twigs sticking out. The idea, I think, came from the Far East. Early teapots were originally imported with tea; they weren’t made in Britain until the end of the 17th century, and even then not very many. These things would arrive, probably buried in tea leaves, and the reaction must have been, ‘So this is a teapot? Gosh what funny handles!’

Before long the industry was infected with these outlandish designs that weren't even their own, and that idea always amuses me. I wanted to reflect their ideas of growth, but at the same time I didn’t want to copy them. So I stylised them, simplified them, made them more of my own time. Taken out of their original context, they have developed their own quirkiness, their own sort of abstraction.

Where I live in Monmouth they don't cut and lay their hedgerows very often, usually bashing them down with a big flail instead. These mutilated hedges then start to sprout and by autumn they've grown at least two feet. You get these wonderful, knobbly joints developing which give the hedge a fabulous character, and many of the dishes I've done over the last few years have referenced that; they've been much more ‘twigiferous’, with lots of stems sticking out everywhere, bashed off to a level.

GG:

Many of your pots have an observable personality. Is that something you are conscious of instilling when you’re making?

Keeler:

It’s an interesting aspect of pottery that the terminology is ‘bellies’, ‘necks’, ‘lips’, ‘feet’; they're almost always related to the human body in some way. Often when I'm demonstrating a particular pot that I make, I put the pieces together without adjusting the angles, and I say, ‘What do you think about this pot? What’s its personality?’ Usually, it looks a bit down: it’s a depressed pot, it's meek, bashful, not very proud. So you say, ‘Let’s change the angle and slope it back a bit,’ and suddenly it’s more cheerful. There is that wonderful element to making a pot that you can change its personality: you can make it more or less engaging.

My extruded jugs don't stand at any particular angle, unlike a thrown pot, which is more or less vertical. An extruded piece can be at whatever angle you happen to cut the base at, so that's a big decision to make, and a very small measurement can change the character of the pot dramatically. Knock five millimetres off the back edge, and suddenly it perks up.

That aspect of my pots is important, the fact that they do have a sort of attitude. The other beautiful thing a pot can do is invite you, it can say, ‘Come on, come and see what I’m meant for.’ I like the idea that you don't need to look at the book of words to find out that it’s a jug and that you should pour from it - it should just ask you to do it.

GG:

What qualities do you look for in your own work?

Keeler:

One word that always comes up when I'm looking at work of any sort is authenticity: is it a genuine attempt to make something that reflects one’s intentions. Of course you can't expect to achieve what you intend precisely every time, and quite often you realise something that wasn't intended but which is probably better than what you had envisioned. But I'm looking for something that convinces me at least that I was trying to find something, and that to an extent I found it.

Most of the time it's much less tangible than that, and often you're surprised by what you've made. For this exhibition I've produced some deeply grooved extruded jugs with particularly whacked-about handles, and they pleased me because I find it very hard to be free. I love the idea of freedom in clay because clay is so rewarding when you treat it freely. But that freedom can't just be reckless; it's got to have purpose. So, with the handles, I extruded them and then attacked them with bits of snapped-off wood, and they became something quite communicative. As with any mark-making instrument, whether it's a brush or a twig or whatever, you mark it in a gestural way, and that not only tells whoever looks at the work how you moved your arm, it also tells them how hard or soft the clay was, what sort of clay it was. It's a very revealing way of working, and when it succeeds it's extremely rewarding.

That's what makes it all so worthwhile, the challenge of working with this crazy stuff. At any stage, whether it's leather hard or whether it's soggy wet, it's just so responsive and so rewarding. And so bloody frustrating!