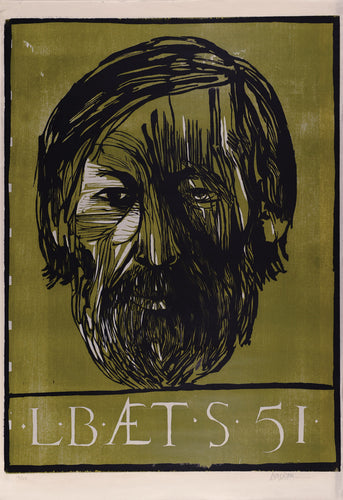

Solemn; dignified; composed; Leonard Baskin's wistful portraits of the 19th century Sioux chieftains remind us of the great maltreatment of these stoic people, and of the power of morally charged art.

An American of Jewish descent, Baskin was one of the universal artists of the 20th century. Principally a sculptor, he was also a superb and prolific print-maker, his output ranging from woodcuts to lithography and etching, with subjects as diverse as portraiture, still lives of flowers, biblical, classical and mythological scenes.

two of Baskin's Native American Chieftains, 'Chief White Man' (left) and 'Quanah Parker' (right)

two of Baskin's Native American Chieftains, 'Chief White Man' (left) and 'Quanah Parker' (right)

By the 1970s Baskin was nearing the midway point of his career, but in spite of his professional accomplishments he remained frustrated with both his work and that of the wider art world. Formalism, the theory that art’s value is determined solely on the aesthetics of its design, medium etc, had become a major preoccupation of his contemporaries, a movement which Baskin felt inappropriately absolved the artist of moral or ethical responsibility, and he was beset by the idea that he might (with his newfound success) lose sight of his own visual integrity.

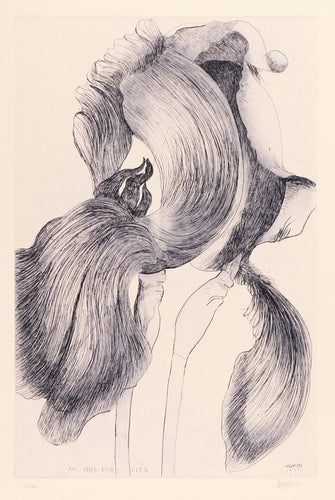

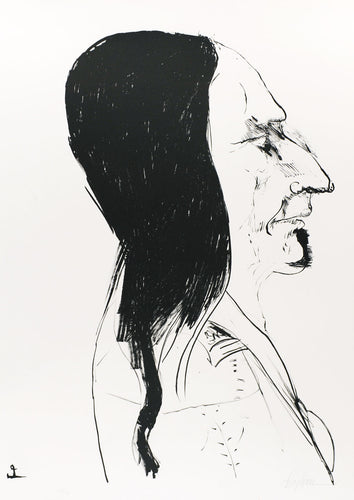

'White Horse'

'White Horse'

When the National Park Service commissioned from Baskin illustrations for the handbook at Custer National Park, now Little Big-Horn National Park, his indignation at the art world’s moral indifference was redirected toward what he saw as the contemptible figure of General Custer and the indifference with which the Sioux Native Americans there were viewed.

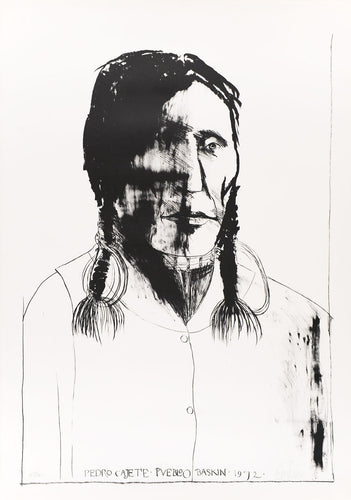

'Pedro Cajete' (left) and 'White Man Runs Him' (right)

'Pedro Cajete' (left) and 'White Man Runs Him' (right)

Inspired by their wisdom, cultural beliefs and the difficulties they had had to face, not helped by the prevalent clichés and stereotype-informed views of the general American public which Hollywood had exacerbated, Baskin began two series of lithographic portraits of the 19th century Native American chieftains.

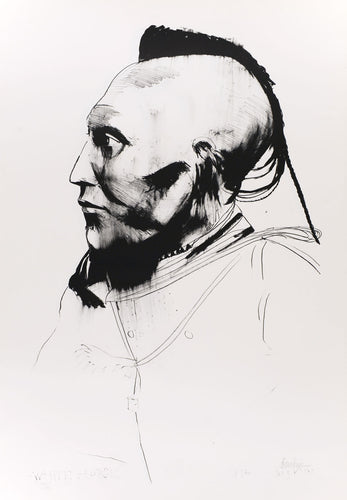

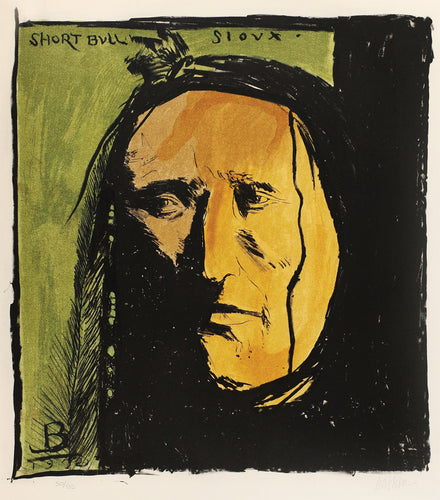

'Short Bull'

'Short Bull'

Indicative of Baskin’s artistic concern for ties of tradition, and for the pervasive general racist, unjust attitude which American society had predicated on its own general anxiety, the suite was bestowed with the formal dignity befitting European royal portraiture of old, and has been widely praised by scholars of Native American history and art.

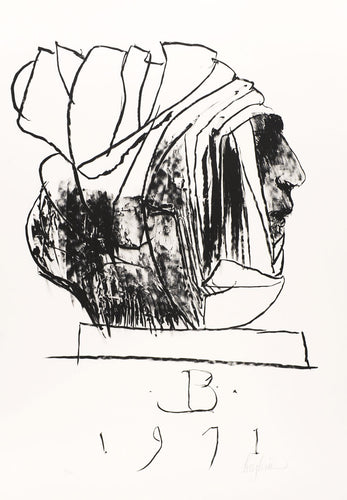

(above) 'Sitting Bull' (left) and 'Chief Wets It' (right); (below) 'Sharp Nose'

(above) 'Sitting Bull' (left) and 'Chief Wets It' (right); (below) 'Sharp Nose'

With prints both in colour and black and white, each chieftain face hides a multitude of emotions, many of them Baskin's own. The peaceful gaze of Sharp Nose is undercut by the deep contrast between both sides of his face, the right-hand side plunged almost into total darkness, a ghostly effect highlighting the history of extinction behind this series of portraits.

'Wolf Robe'

'Wolf Robe'

Undeterred by the artistic trends which emerged from the post-war period, Baskin was unremitting in his artistic integrity: at the heart of these portraits, as at the heart of all his work, are an honesty and humility which here calmly offer the Native American ancestry the respect it had deserved.