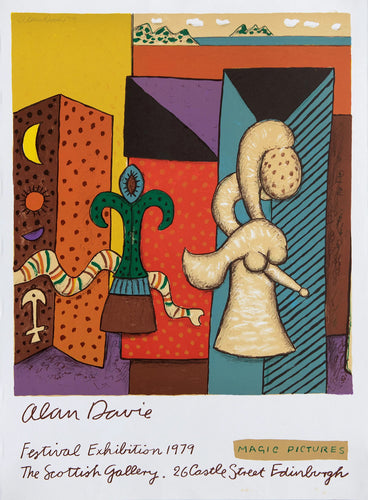

'Lovers' Dreamboat No. 17', oil on canvas by Alan Davie

They shared a patron in the great Peggy Guggenheim, whose collection of masterpieces by Braque, Klee, and Kandinsky had first inspired the young Davie to paint. His output was prodigious and profuse from the very start: within months of witnessing Guggenheim’s collection exhibited at the 1948 Venice Biennale, Davie had produced enough work to fill two solo shows. An encounter with the collector herself saw two of his canvases join works by his American contemporaries - Pollock, Rothko, Klein, and de Kooning - in the legendary Guggenheim estate.

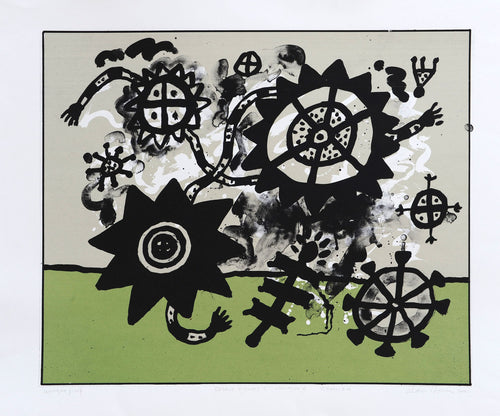

'Tresor Fone Variation No. 5', screenprint demonstrating Davie's symbolism

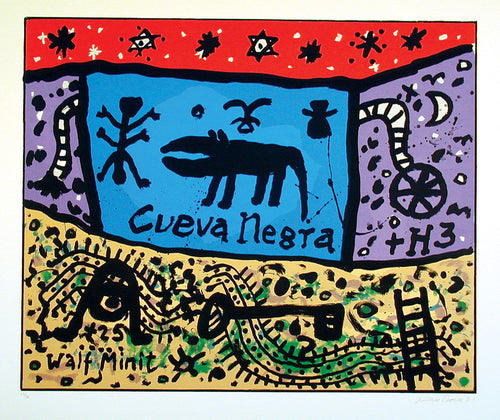

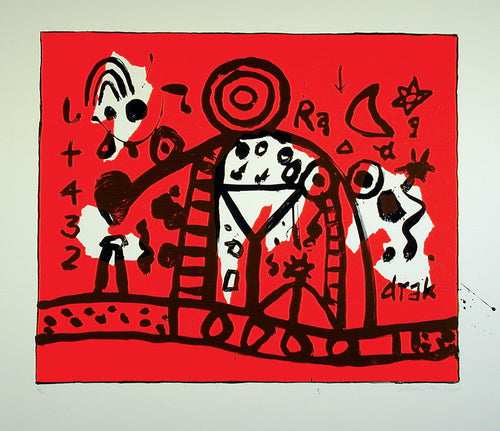

Unlike the New York school, Davie was never tied to the dogma of pure abstraction, nor did he limit himself to any one stylistic approach. In his early career, much like the Americans, he painted with gestural abandon; by the late 1960s and ‘70s, his brushwork was more defined and deliberate. Explosive colour remained a constant, as did the need to work spontaneously. He painted with exceptional speed, attempting to escape any notion of preconceived composition and allow a subconscious, Zen-like state to direct his hand. To stimulate the creative process he often used liquid paint, removing canvases from their easels and attacking them on the floor – a style of ‘action painting’ that Pollock was exploring at the same time but which Davie arrived at quite independently.

By the early 1970s, when Lovers' Dreamboat was produced, Davie had developed a powerful symbolic vocabulary. His fascination with symbols derived from their universality, the idea that pictograms and iconographies had been shared between different peoples over many thousands of years. Relocated in Davie’s work, these same icons found new personal resonances. Dreamboat's Coloured flags – bold geometric forms in their own right – invoke semaphore signs and Tibetan prayer flags (Davie was both a sailor and a Buddhist). To their left stand two sculptural totems, inspired perhaps by the carvings from Davie’s own collection of African and Oceanic art. Other elements seem almost psychoanalytic: a crescent moon floats above, a key visual figure within the Surrealist idiom; behind lie the open window and door, suggestions of a room that leads only to otherworldly blackness.

To Davie, the power of the symbol was not that it represented a certain something, but that it could represent anything, and more than one thing at a time. His own art is much like mankind’s greatest symbols: potent, mysterious, instantly recognisable, and offering a multiplicity of meanings.