Like Kandinsky, whom she had translated as a student, she was the cofounder of a major avant-garde movement – the poetically named Orphism – and saw in art the basis of a universal language. Her astonishing manipulation of colour was grounded in ocular science and her own aesthetic theories. But, more importantly, Delaunay would transcend the theoretical; in addition to producing some of the most important nonfigurative art of her generation, she designed costumes for the theatre and haute couture fashion. Her rhythmic circles and squares spilled from canvas onto textiles, furniture, film sets and fast cars. Art and colour infiltrated every corner of her life, from the poems and paintings that decorated her apartment walls to the coats and dresses she paraded in the streets of Paris.

Abstract Fashion Design, pochoir

Little is known about Delaunay’s early youth. Born Sara Stern to Ukrainian Jewish parents in Odessa, 1885, as a child she was sent to live with her wealthy aunt and uncle in St Petersburg, whose named she adopted, becoming Sonia Terk. She was, judging by the few diaries and letters that survive from the time, a bright, cerebral young woman, quick to learn and eager to expand her experiences beyond the comfortable, cultured upbringing she had enjoyed in Russia. By fourteen she was already a polyglot, reading Voltaire, Goethe, and Shakespeare in their original languages. At the age of nineteen, she left for Germany to study painting. Two years later, in 1906, she was already on the move again, this time to Paris, where she enrolled at the Académie de la Palette.

Delaunay travelled and read with a restlessness that was evident in her early paintings too. Within just a few years of study, she had assimilated the powerful, primitivist sense of form explored in German Expressionism, and in Paris came face to face with the violent colour of the Fauves. Her first major works – provocative, angular studio portraits and posed nudes – were worked in virulent colour: hot pinks and sour yellow underscored by shadows of sea green, a palette that betrayed the strong influence of Gauguin. In 1908 she married the critic and collector Wilhelm Uhde, but the marriage was a sham; it secured Delaunay’s stay in Paris and provided Uhde, a closeted homosexual, with an out, but by 1910 she had met Robert, a young, aristocratic painter who seemed to share so much of her artistic vision. She divorced and remarried later that year, giving birth to their son in January of 1911.

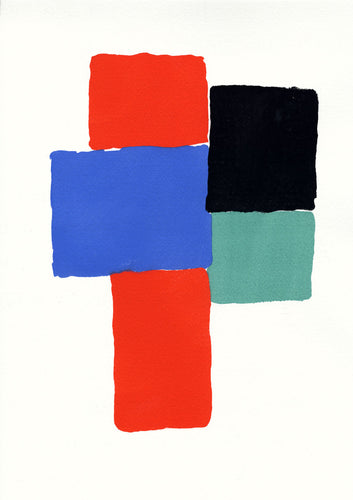

Box Design, pochoir

For most gifted female artists of the early 20th century, the burden of a child and a painter-husband might mark the end - the subsuming of a promising career beneath that of her male counterpart. For Delaunay, this was just the beginning. Soon after giving birth to her son, Charles, she took up embroidery and fashioned for him a quilt for his cot. Its multicolour, chequered design was to change their lives forever: ‘I had the idea of making…a blanket composed of bits of fabric like those I had seen in the houses of Russian peasants. When it was finished, the arrangement of the pieces of material seemed to me to evoke cubist conceptions and we then tried to apply the same process to other objects and paintings.’

Fabric Designs, gouache, (left) 'Geometric Fashion Design'; (right) 'Red and Blue Flowers on Black'

This was the birth of the abstraction and colour theory that would inform the two Delaunays’ art for the rest of their careers. Their approach was founded in part upon the ‘Simultanism’ of Michel Eugène Chevreul. Chevreul had found that when two colours, contrasting or complementary, were placed beside one another – when they were ‘simultaneous’ – they were experienced differently: a yellow, for example, might appear visually brighter on a black background than on a light grey one. Published in the late 1830s, Chevreul’s theory had over time found its way into the hands of the Impressionists and their successors, who began not to mix paint to achieve certain hues but to place strokes of primary colour beside one another such that the eye performed the ‘mixing’ itself.

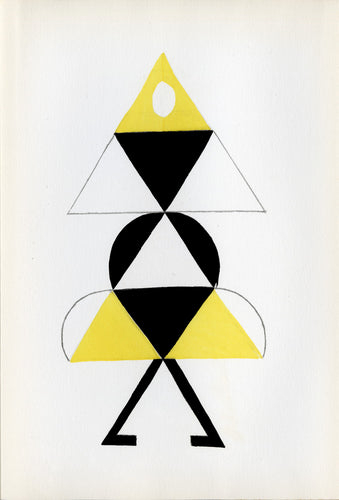

'Marine', pochoir with pencil

Delaunay was fascinated by colour. Like music, she saw in it the potential for a truly ‘universal’ expressive language, and even experimented with assigning vowels and other linguistic units specific shapes and shades. To the critic and poet Apollinaire, a close friend of the Delaunays who had stayed with them in Paris and wrote of how they seemed to ‘speak painting’, Sonia and Robert’s cubist applications of colour resonated with musical and poetic vibrancy: he termed this new art ‘Orphism’, in reference to the mythic Greek singer whose song silenced Sirens, animated rocks and trees, and charmed even Hades himself with its beauty.

Delaunay swiftly developed her ‘Orphic’ style in loose, geometric paintings with concentric circles and quivering arcs that reflected the bright, bustling modernity of pre-war city living. She painted wooden furniture for their rue des Grands-Augustins flat and made ‘simultaneous’ suits and dresses which she and Robert wore to Parisian nightclubs, flaunting their new style on the dancefloor. Forced to flee to Portugal during the First World War, her predicament was made worse with the Russian Revolution in 1917, which effectively brought an end to her small source of family income. Ever the shrewd businesswoman, she seized the moment as both a financial opportunity and a way to disseminate her colour theories across a multitude of new media, creating her first boutique, the ‘Casa Sonia’, and later registering ‘Simultané’ as an official brand name.

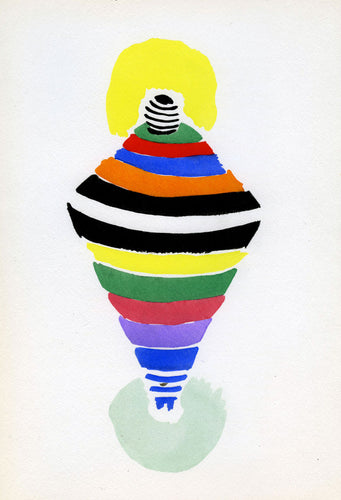

'Costume pour carnaval de Rio', pochoir

Delaunay’s bridging of the divide between the rarefied spheres of modern art and the world of craft, fashion, and design was perhaps the most successful of any other artist of the 20th century. Her balance of colour and geometric pattern translated with ease to fabrics for clothing and upholstery. Designs for garments were produced as pochoir prints, a luxurious, time and labour-intensive process in which colour was hand-brushed through successive layers of stencils to build up a final image.

Initially these designs were presented in couture brochures, but Delaunay evidently relished the clarity and depth of colour attainable in the process: she continued to use pochoir in her many illustrated books, collaborating with contemporary poets such as Blaise Cendrars or illuminating the words of writers past, such as Rimbaud (with whom she felt a particular affiliation) in celebratory sweeps, dashes, and blocks of pure colour. Though almost exclusively abstract, she claimed her work was always rooted in reflection on the world around her, and not merely formal or intellectual: ‘Direct observation of the luminous essence of nature is for me indispensable…’

In the inter-war years, Delaunay’s output was phenomenal: her fabrics were now sold worldwide, and her theatrical projects included set and costume designs for Tristan Tzara and performances by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, as well as commissions for a host of French films. Most emphatic was her influence on the world of fashion, with a Vogue cover design in 1926 and outfits for members of high-society glitterati. Unlike other artists, whose attempts at straddling the art / craft divide dissipated into the overly decorative, Delaunay’s stylised fabric prints were as forceful and thought-through as her contemporary canvases. This was not a woman artist relegated to the ‘feminine’ worlds of clothing and interiors: Delaunay was a pioneering artist-designer, relocating serious abstract art to the wider public realm and fusing modernism with the everyday; in this aspect, she proved far more adventurous than her celebrated husband.

Robert’s death in 1941 from cancer left her bereft, not just of a life partner, but one with whom she had shared an artistic vision from the very earliest months of their marriage. She would not paint for another ten years, returning once more to large canvases and illustrated books in the post-war period. In 1964 she became the first living female artist ever to be afforded a retrospective at the Louvre, cementing her reputation as an outstanding modern artist, still exploring the harmonies of interlocking colour and form even in her final years.

A major recent evaluation of her work at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris and the Tate in London reaffirmed that, far from diluting the power of her art through its diffusion across so many different projects, Delaunay’s multifaceted nature was central to her success. She would influence artists for years to come, from the social conscience of Op Art to the creations of the modern-day catwalk.