When readers of the Alice books first opened their pages, the faces that greeted them might have seemed familiar. Was that Disraeli, leader of the opposition, hosting a tea party? Our editor heads down the rabbit hole to see how politics and pantomime inspired John Tenniel’s magical illustrations.

The Green Room, photograph by the London Stereoscopic Company of performers at a benefit for the widow of Charles Bennett at the Adelphi Theatre, 1867, collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The Green Room

In the commodious trove of the Victoria & Albert Museum there is a rather wonderful photograph taken by the London Stereoscopic Company of John Tenniel and his colleagues at Punch, outfitted with 17th century flourish for an amateur dramatics event (the National Portrait Gallery have a signed copy, too). The performance had taken place at the Adelphi Theatre in May 1867, with all proceeds going toward a benefit fund for the family of the late Charles H. Bennett, one of the illustrators for what was then Britain’s premier satirical magazine. Ill health and poor finances had precluded him from medical insurance, and he left behind him 8 children and a pregnant wife: fortunately, the event was a roaring success.

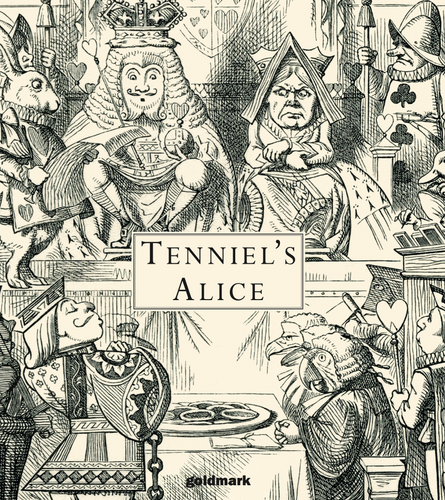

John Tenniel, The King and Queen of Hearts were seated on their throne..., woodcut

The evening opened with a one-act comic operetta, Cox and Box, put to music by a young Arthur Sullivan, later of Gilbert and Sullivan fame: you can see him here, seated on the left, admiring his fellow performers. W.S. Gilbert, his future colleague, reviewed the performance in his Fun magazine, one of Punch’s main rivals, bringing the names Gilbert and Sullivan together several years before their first collaboration. But the main event was a stage play written by Tenniel’s friend, Tom Taylor. A Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing, as the comedy was titled, takes place during the bloody days of the Glorious Revolution. The Monmouth rebellion has been thwarted, and the dastardly Colonel Percy Kirke (played by Punch’s portly founding editor, Mark Lemon, fourth from left) has been sent to exact retribution in the West Country, where the charismatic rebel Jasper Carew hides himself in his family home. Reviews confirmed that confusion and hilarity ensued.

You’ll find Tenniel here in the back row of this tableau, third from right, replete with magnificent moustache. Standing and seated around him is a fascinating snapshot into one of London’s literary and theatrical cliques. Punch colleagues Robert Pritchett (illustrator, back left), Henry Silver (writer, back right), Shirley Brooks (writer and future editor, second from left) and little George du Maurier (writer and illustrator, seated centre on floor) are joined by theatre royalty in the form of a young Ellen and Kate Terry (seated, left and right), actors and artists’ models of note. Actors Arthur Cecil (second from right), Arthur Lewis (third from left), and Quintin Twiss (fourth from right, an old college friend of Lewis Carroll’s) round out the cast, while seated front right, looking straight to camera, is Tom Taylor, writer for Punch, author of the evening’s play and its protagonist – and the man who three years earlier had introduced John Tenniel to Carroll, ensuring the future success of Alice in Wonderland.

Unseen, but seated in the audience, was Caroll himself – real name Reverend Charles Dodgson, an Oxford mathematician, photographer and author of one of the most enduring works in English literature. He had not long asked Tenniel if he might illustrate a sequel to his first Alice book, but Tenniel had declined (he was later to change his mind). And we also know, from letters to his brother, that at the time of this performance Carroll was contemplating his own stage version of Alice, perhaps a pantomime: ‘I fancy it would work well in that form.’ Seeing Tenniel on stage must have strengthened his vision for the planned second Alice outing, for which he still felt there could be only one worthy illustrator.

A Happy Family

This is not the only piece of Tenniel ephemera in the V&A collection. Alongside pencil sketches for the Punch contributions which by the mid-1860s had made Tenniel’s name, there is a design of Leonardo for the Kensington Valhalla mosaic, an arcade of thirty-five portraits of famous artists made shortly after he was photographed here. It was in this collection that I also learnt that Tenniel was likely the (uncredited) hand behind the very first ‘Happy Families’ cards, commissioned in 1851 by the games manufacturer John Jaques to be unveiled at the Great Exhibition. Like his illustrations for Alice, these designs have remained in one print form or another ever since. I remember playing with a dog-eared pack at my grandparents’ house that dated to the 1970s. Looking back now, of course they are Tenniel: the grotesque big-head styles, influenced by pantomime papier-mâché heads and masks of the commedia dell’arte, are pure Humpty-Dumpty, or the deliciously ugly Duchess.

But I love this photograph especially. Like the best bygone trinkets, it captures a moment in history in all its peculiar specificity. It confirms, for example, how important the brotherhood of Punch had probably become for Tenniel, who was himself widowed in his early 30s, barely a year after he had married. Punch was as much a gentleman’s club as it was a publication staff or a political entity, its contributors a close-knit brood. Surviving records of its legendary ‘Punch Table’ dinners-cum-staff meetings reveal that humour and rib-poking existed beyond the sheets of the publication. Shortly before his death, Charles Bennett’s colleagues on the Punch ‘Council’ (among them Tenniel) gathered to note that they ‘deeply sympathise with C.H. Bennett on the state of his hair’. Illness, impecuniosity and a bohemian streak had prevented him from finding an affordable barber. ‘Anxious to receive the said Bennett to its bosom once again’, the council moved to entrust Mark Lemon, with ‘(limited) confidence’, to secure a subscription to a suitable barber, ‘to the end that he may have his damn hair cut, and rejoin the assembly of the brethren.’

Alice Liddell as ‘The Beggar Maid’, Lewis Carroll (Charles Dodgson), 1858, collection of The Met

More than anything, however, what struck me when I first saw this image was how much it reminded me of Tenniel’s first Alice illustrations: the Queen and King of hearts in particular, presiding over their suited subjects in full playing-card regalia, with their flat and fronted designs echoing both the cards themselves but also the melodramatic, front-facing attitude of players on a stage. There is another curious connection with Bennett here, whose illustration of Man tried in the Court of the Lion, one of his celebrated engravings for Aesop’s Fables, provided the model for Tenniel’s own Alice courtside scene. Both images are almost super-flattened, so that they resemble not just a stage but even a Punch and Judy theatre box. In fact, the longer you look at Tenniel’s illustrations, the more theatrical direction and staging you will see: arrayed limbs across the composition like a tableau vivant, the crowding of characters as of players on the stage, the criss-crossing eyelines of spectators, protagonists arranged in compositional layers of prominence while background settings compress into layers like set designs. (Here’s another cue: look at the feet of any Tenniel sketch and you’ll find them poised with balletic precision). Why did the staff of a satirical magazine find themselves – more than once! – onstage, and how did Punch and the world of theatre end up informing Carroll’s Wonderland?

Child’s Play

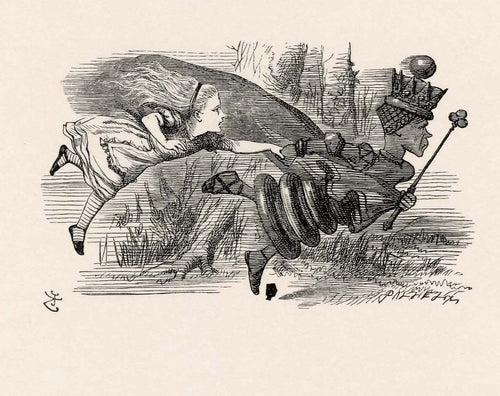

One of the great takeaways from Frankie Morris’ 2005 biography of John Tenniel (a new edition is appearing this month) was the growing prevalence of theatre, pantomime and child’s play in the Victorian public conscience. By the middle of the century, early in its formation, Punch and the theatre were wholly entwined. Its publishers developed close associations with Charles Dickens’ famous amateur productions, and on more than one occasion Tenniel trod the boards with both Dickens and his writing protégé Wilkie Collins. There were playwrights on the Punch staff: Tenniel’s close friend, Shirley Brooks, who would later take over from Mark Lemon as editor and lead it into a Golden Age of satire, was a dramatist of broad theatrical extravaganzas. Invariably the language of theatre, visual and otherwise, with its repertoire of poses, its rich literary referencing, its adaptability to parody and the burlesque, made it ideal re-packaging material for Punch, where in the form of political cartoons or written pastiches it could be enjoyed by a similarly literary readership. Engaging pantomime especially, with its overly telegraphed absurdity, allowed Punch ribald visual comparisons and the opportunity to play with scale, ballooning personalities and shrinking politicians to the size of quarrelling schoolboys. Before long, the politicians were responding with like, adopting the metaphors of pantomime as ammunition in their own despatch box spats (theatrical performances in another guise). On the stage, Carroll proclaimed, everything was ‘bigger than life’: or as Dickens put it, here ‘Everything is capable, with the greatest ease, of being changed into Anything’ – just like Wonderland.

Common to all these men – Dickens, Tenniel, and Carroll – was performance as a key ingredient in their childhood. For the middleclass Victorian child, theatre was a source of play and of playful education, of formal ‘dressing up’, and it has remained so ever since. Tenniel’s battle outfits for the two Tweedles, which were themselves inspired by a fellow Punch cartoonist, are exactly the kind of ramshackle agglomeration of props and paraphernalia that characterise children’s Nativities and amateur productions today.

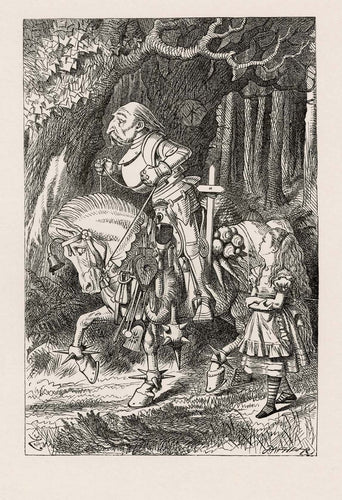

For Tenniel, theatricality came in the form of a childhood growing up with a father who fenced and danced, and taught both to his children (an accident while sparring with his father when he was just 20 actually left Tenniel near blind in his right eye). A young student of the Royal Academy, he had quit ‘in utter disgust’ at the deficient practical teaching he received there and instead turned to a world of antique costume and the stage for inspiration, sketching suits of armour and matinée actors at work. By the time Tenniel had become Punch’s lead cartoonist in 1864 he harboured a love of exaggerated Arthurian chivalry, delighted in period costume, and in his cartoon style indulged a penchant for Gothic revival: knights in shining armour, inspired by the example of Dürer (as a young man he had left to study fresco technique in Munich under the German painter Peter von Cornelius, leading to what Morris called his ‘Teutonic’ streak). This you can see in both his Punch cartoons and his Alice illustrations. The bridle and saddle of the White Knight’s Germanic steed bristle with an array of props designed to hint at other episodes in Alice’s journey through Wonderland. While we are here, is the knight (as is often suspected) a portrait of John Tenniel himself? The V&A photograph reveals Tenniel had his moustache by then, but the knight appears much older than Tenniel was here, entering his late 40s. Later in his career, when he was eventually knighted for his services to illustration – the first cartoonist to receive such an honour – his colleagues invariably celebrated the moment by depicting him as a whiskered knight astride a dappled steed, so that the resemblance (however slight) became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In Carroll’s case, performance began at an early age when he was gifted a marionette case with which to entertain his many siblings. The Alice story itself famously began life as an improvised tale, recounted to a young Alice Liddell to enliven an Oxford boat trip. But it was perhaps his private work as a photographer, which supplemented his academic career and involved the kind of careful orchestration of a stage director, that demonstrated Carroll’s real understanding of the medium. These photographs of young children, either costumed or nude (the jury is still out on the nature of some) were concerned, like Alice, with preserving a kind of prelapsarian Eden of childhood days.

Alice herself is a thoroughly realistic, and un-Victorian, child protagonist, in the mould of the intellectual and steadfast Jane Eyre or Thackeray’s picaresque Rebecca Sharp of Vanity Fair, who enters an unfamiliar world of regency manners and navigates its snares with guile to outshine the sweet and simple Amelia Sedley. How does Vanity Fair begin? Before a curtain rise, with the manager of a travelling puppet show surveying the assembling audiences at the ‘vanity fair’. And before the success of Vanity Fair, how had Thackeray maintained his writing career? As a writer on the staff of Punch.

Like Becky Sharp, there is bite and cunning to Alice; as a child, she retains a mixture of innocence, naivety and unwitting cruelty, as when she terrifies the birds and rodents of Wonderland with descriptions of her pet dog, Dinah. She is of course curious, brave, proud and occasionally intemperate, talkative, sometimes self-absorbed, often frustrated, and has endured into the 21st century all the better for it besides the wan and drippy Pre-Raphaelite maidens who were her visual contemporaries. In her poem In An Artist’s Studio, Christina Rossetti, sister of the artist, described these languid models imprisoned in the role of the muse, ‘A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens, a saint, an angel’ subordinated to the frame of an artist’s eclipsing gaze: not so with Alice.

Charles Bennett, Court of the Lion from Aesop’s Fables, 1857; this engraving may have inspired Tenniel’s own court scene in Alice in Wonderland

The weirdness of Wonderland

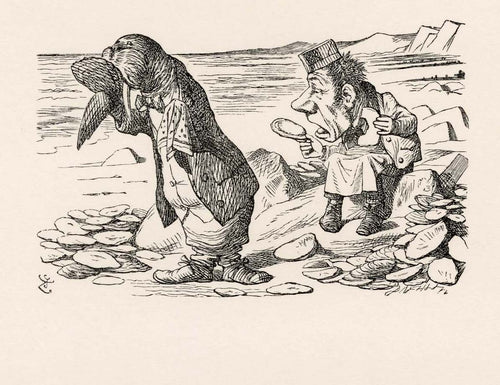

The satirist and the playwright are both bound, and liberated, by the same limitation to the imaginable. Theatre’s limitation is its physicality: what can be achieved within the scope of the stage, the set and costume design, the mechanics of the playhouse. Satire’s limitation is relevance: if its reference points are unintelligible, or the images so far gone into the dreamworld that they become utterly divorced from reality, then it fails at the first hurdle. The sort of tricks we might expect from a pantomime on the stage – animal anthropomorphism, transformations in dress, stretching shapes and sizes, and absurdist behaviour – all lie within the cartoonist’s remit. Though Tenniel and Carroll were referencing different traditions as they completed their contributions to the Alice books, through theatre and satire they were often drawing from the same playbook.

Happy Families, ‘a new and most diverting game for juveniles’ from John Jaques & Son, Ltd.

Alice’s two adventures in Wonderland combine a classic ‘fish out of water’ outsider’s story with a gentle academic satire of arbitrary rules and rationalisation. They can be read as a lampoon of the British court system, of Oxford college life, of mathematics and teaching, of etiquette, and of language. Alice’s befuddlement at the strange internal logic of Wonderland in some ways echoes the perspective of a child growing up and encountering the strict world of adults and their various coded rules, some less obvious and less explicit than others. Carroll’s text plays and probes at the contradictions in idiomatic speech and proper logic. It’s not just that the longer we spend in Wonderland with Alice, the stranger it seems; more than that, the stranger our own world, and its assumed way of doing things, appears. In this, the books shared the fundamental basis of Tenniel’s satirical cartooning: absurdity, disbelief and disorientation shake us to the problems of the present. The longer Alice is confronted by the ridiculousness of Wonderland’s way of doing things, the less forgiving she is of its weirdness and humour gives way to frustration, much as a political cartoons might point to real and significant injustices.

Tenniel’s borrowing from the world of the stage for the Alice illustrations makes all the more sense when you read the Alice books aloud, for they are largely discursive: like one of Plato’s Socratic dialogues gone wrong. The chapters are often conversation heavy and detail light, with a peculiar knowing relationship with their audience as the narrator – Carroll himself – turns to address us (as he did when first relating the tales to Alice Liddell). Chapter VII of Alice in Wonderland – the Mad Tea-Party – is distilled theatre, as if made for the stage. We have the long, laid-out table facing the audience, the near constant repartee, the slapstick cycle of changing places. Sometimes the text between conversations is almost direction-like, as an actor might expect to read in a script. Were it not so fantastically transformative, it would – as Carroll anticipated – make for a fantastic stage-play. And yet, as Walt Disney was to discover, its narrative would not always be easy to sustain.

Linley Sambourne, The Black-and-White Knight, engraving in Punch, 1893; a tribute to Tenniel’s knighthood

‘What use,’ says Alice, ‘is a book without pictures?’ It was Tenniel’s task to set the stage, as it were, and to costume Carroll’s personalities. His tenure at Punch began in exciting political times as the machinery of Empire moved across the globe. He recorded the rise of Benjamin Disraeli, ‘up the greasy pole’ as ‘Dizzy’ put it. The two Alice books would fall either side of Disraeli’s first failed term as Prime Minister and the transition of power from his Conservatives to Gladstone’s Liberals. Here the stage would provide again the perfect metaphor of political players ‘waiting in the wings’. In one cartoon made shortly after Disraeli’s first term began, the new Prime Minister adopts the role of Hamlet, practising his monologues, while Gladstone fumes in the background. ‘A time will come!’ Gladstone declares; within a short ten months he was right.

By the time Tenniel was producing work for Carroll, Punch was as much an institution as the establishments it caricatured. Its popularity was due in part to reserve combined with irreverence, probity with non-partisanship, and it was sufficiently respectable as to be found in the quarters of bachelor deacons and Oxford dons, such as Carroll himself. As a cartoonist, Tenniel relied almost entirely on his trained memory, rather than drawing from life. As every object of an illustration was his own invention, he could endow each with individual personality, like a caricaturist, whether it was a person, an animal, or a piece of furniture. But he was also a magpie, with a voracious appetite, forever revisiting and recycling and regurgitating what he had drawn and what he had seen drawn elsewhere, whether his own ‘cuts’ or those of his colleagues. Many writers have enjoyed tumbling down the rabbit hole of tracing pedigrees in the Alice illustrations: is the Mad Hatter, or the goateed man dressed in papers in the train carriage, a stand-in for Disraeli? Not in any political sense, I suspect, but there’s certainly a likeness there. The same familiarity we feel encountering Tenniel’s Alice received down the line in later adaptations is the familiarity readers of Punch (or theatregoers) might have had encountering Tenniel’s illustrations for the first time, and recognising familiar faces, poses, and details. But among my favourite of the Alice illustrations are those with little relation to anything that had come before in Punch, but which depended on the same capacity for realistic transformation: the tiny imagined insects, assembled from leftover pieces of food, for example, or the wonderful hookah-sucking caterpillar. Here Tenniel finds exactly that place within satire’s imaginative limitations, the sweet and disturbing spot between realism and grotesquery that can set teeth on edge. The caterpillar holds the hookah pipe to his lips – except that his face is simply a clever arrangement of his first six squat legs in the shape of a mouth and a hood. The result is a head that, from the back at least, resembles the Punch mascot in his floppy cap: how he might appear from the front is left to your imagination.

![John Tenniel, Rival Stars, March 1868; the caption reads: Mr Bendizzy (Hamlet): ‘“To be or not to be, that is the question” – Ahem!’ Mr Gladstone [Aside]: ‘“Leading business”, Forsooth! His line is “General Utility” Is the manager mad? But no matter-rr – a time will come –’](https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0554/5597/3514/files/Screenshot-2023-06-29-at-15.54.27.jpg?v=1688050496)

John Tenniel, Rival Stars, March 1868; the caption reads:

Mr Bendizzy (Hamlet): ‘“To be or not to be, that is the question” – Ahem!’

Mr Gladstone [Aside]: ‘“Leading business”, Forsooth! His line is “General Utility” Is the manager mad? But no matter-rr – a time will come –’

Alice After Tenniel

Within a year of its copyright expiring, more than sixteen new editions of Alice in Wonderland would emerge in England alone. It was a sign of their cultural currency that Tenniel’s illustrations had not just stolen from Punch and his own cartoons, but would go on to inspire future features in the publication, continually referenced after Carroll’s death and even after Tenniel’s own. In the century since, Tenniel has had to contend with Disney, Dali, and Tim Burton; still he remains untoppled as the preeminent illustrator of Carroll’s now ubiquitous text.

Ever the Victorian gentleman, Tenniel appears to have given little thought to his own royalties. Even during his lifetime, Carroll was writing to ask his permission for various merchandising and franchising schemes for which Tenniel was never paid. With no wife or children left behind him, it’s unclear where that money would have gone anyway. But the commodification of Alice has become a story in its own right.

Cary Grant nurses his 1933 Mock Turtle mask

Besides Tenniel, only Disney, by sheer monopolising command of the animation market, has come close to cementing a visual interpretation of Carroll’s texts in the public consciousness. His version eventually arrived in 1951, but in fact some of his earliest films – made some 30 years earlier – with which he built his reputation were based on the model of Alice. An animated version might have been Disney’s first major motion picture film, had rivals at Paramount not released their own live action version in 1933 (starring an unrecognisable Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle.) Aldous Huxley was named as a possible scriptwriter, but nothing came of the project and it was left to sit until the late 1940s. There is a reason the trailer for the 1951 version opens with the phrase, ‘At Last!’

In the end, Disney’s Wonderland emerged with an entirely different aesthetic (and one that the critics panned). Using Tenniel as a model, as he had intended, proved problematic: his crisp, linear quality proved untranslatable to hand-drawn animation. And so the vibrant, eclectic version moulded by the concept artist Mary Blair replaces with psychedelic pattern and colour his clarity of line, inspired by Latin American folk art.

still from Walt Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, 1951, with background and concept art by Mary Blair

Without the line, there is no grotesquery, and something of the edge that was in Alice, and in Tenniel’s illustrations, has rarely been recovered. The Czech auteur Jan Švankmajer’s Něco z Alenky (‘Something from Alice’), which combined real time and stop motion with deranged puppetry, leans heavily into the Surrealist fever-dream elements of Carroll’s original text, returning it to the realm of the unconscious from which it had first emerged. But most re-adaptations have suffered the same problems: that there is no threaded narrative to Alice’s journey which, like a dream itself, seems to melt from one mental exercise to another. Interestingly, most of us can recall its central characters, and even its internal episodes. But how many could describe, from start to finish, the plot of either book?

Though Carroll is now the better known author, and the language of Alice has fully permeated everyday speech, it is Tenniel who has cemented the vision of Alice in our heads, who gives form to childhood memory and whose aesthetic has continued to influence for over 150 years. ‘In a ghostly way,’ writes Michael Hancher, chief sleuth of the influence of Punch on Alice, ‘Tenniel retains something of his original precedence over Carroll.’