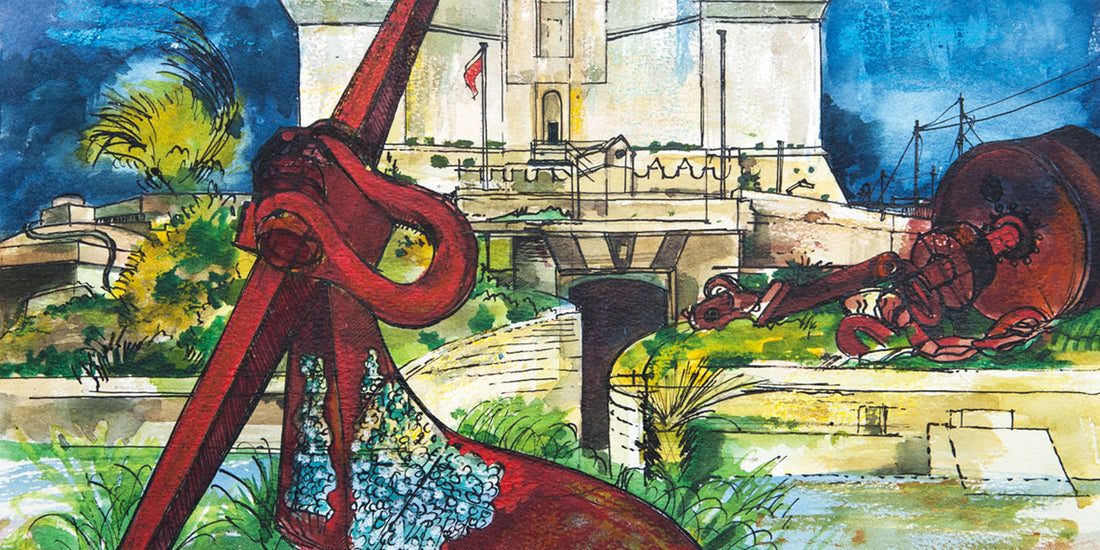

The Maltese landscape is not kind to the outdoors painter. This is especially the case when one’s chosen subjects are abandoned limestone quarries, archaeological ruins, dilapidated churches and wartime bunkers. High winds whip up clay and chalk-dust; cactus thorns hook at trouser legs and catch on ankles. Closer to civilisation, the hot reek of rubbish bags attacked by stray dogs and the persistent pestering of locals and tourists make concentration and quiet an impossibility.

Landscape with Girna, 1995

Landscape with Girna, 1995

Yet this is exactly the environment in which Rigby Graham – a man for whom defiance became a full-time occupation - would sit, rooted to a portable aluminium chair, and paint in vivid colour.

the artist at work, characteristically sat in the hedgerow beneath native prickly pears

the artist at work, characteristically sat in the hedgerow beneath native prickly pears

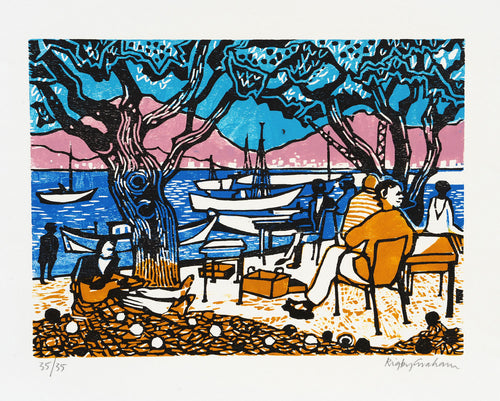

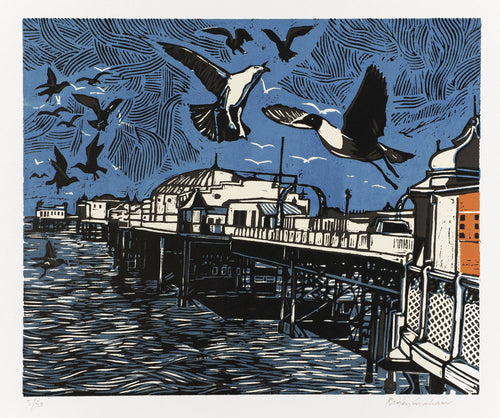

Directness and a lack of pretence typified all aspects of Graham’s life, none more so than his watercolours. A disciple of the school of Minton, Place and Towne and a young contemporary of Piper and Sutherland, artists who reinvigorated the English school of watercolour painting, Graham was drawn to the medium’s immediacy and returned to it regularly throughout his long career. Such painting was always undertaken outside and ‘in the moment’, making of each work a record of the place, the experience and all its concomitant frustrations: heavy rain, gales, an undergrowth that fought back; difficult weather and scenery, and the even more difficult temperament of the artist.

(above) Selmun Palace, 1995; (below) Quarry, Luga, 1994

(above) Selmun Palace, 1995; (below) Quarry, Luga, 1994

Dereliction remained a favoured subject of Graham’s. Historical landmarks were painted from perspectives that saw much of the main subject obscured, either by eye-height nettles, barbed-wire, pylons, telegraph poles, or wire cables drooping and slicing across the sky overhead. Unlike the idealised vision of idyllic countryside presented by many working in the topographical genre, Graham’s landscapes bristle with evidence of the human impact on place over the last hundred years, what he termed ‘our detritus’: I never need to look for such things; they are everywhere. Most people are immune to them or only notice them exceptionally. Just as in this country there are more rats than human beings, so too I believe there are probably more poles, pillars, pylons and fence posts than rats.

details of crumbling ruins at Xaghra (above, 1995) and Windmill, Xarolla (below, 1994)

details of crumbling ruins at Xaghra (above, 1995) and Windmill, Xarolla (below, 1994)

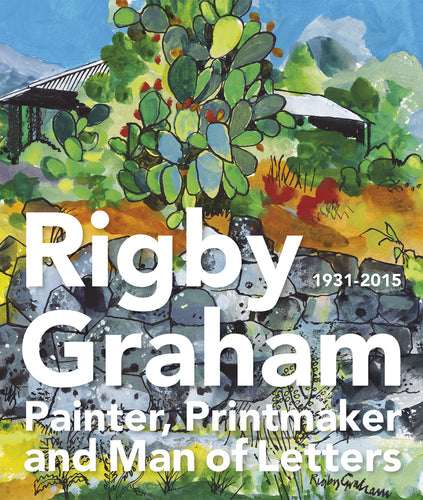

Graham was frequently attracted to the Mediterranean island rock of Malta, where he had become acquainted with local poets Charles Flores and Victor Fenech. From 1970 until his recent passing in 2015 he visited the island seven times, producing over ninety watercolours of varying subjects unrecognisable to the casual tourist: monolithic rock formations, crumbling ruins, and view lines from gritty coastal stretches that look up past wire fences at the fortifications above. In 2008 a number of these paintings were compiled alongside poetry by Fenech to present a quite different image of the post-colonial destination than the panoramic views presented to visiting sightseers.

(above) Fort St. Lucian, Marsaxlokk (1995); (below) detail of barbed wire and detritus on Manoel Island, 1994

(above) Fort St. Lucian, Marsaxlokk (1995); (below) detail of barbed wire and detritus on Manoel Island, 1994

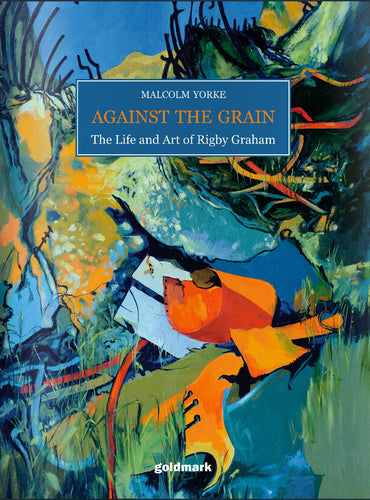

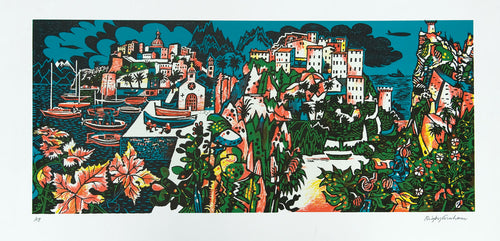

While a great many of those who choose watercolour as their medium either muddy their colours, blending paint until it loses all vibrancy, or water down to an anaemic wash, Graham’s work was always wrought in rich, bright, and often unmixed primary colour. As Malcolm Yorke describes in his biography of Graham’s life and art: [Those] accustomed to the British watercolour tradition, or to seeing genteel offerings at the Royal Academy Summer Show, recoil in shock on entering a gallery of Graham’s work. Where, people ask, did he find all these tart greens and citric yellows and pepper reds? Why is the sky scarlet or green, the rocks blue, and the sand so primrose? In short, his watercolours put the stress of the colour, not the water.

Wied il-Ghasel, 1995

Wied il-Ghasel, 1995

Few native landscape artists can lay claim to the strength of vision and the conviction of touch that characterised Graham’s work. In his lurid reds and yellows, sapphire blues and shocks of green all tamed by an assertive black pen line, he brought to an all-too-often tired category of painting an energy that was sorely lacking. We are confident that, with the passing of time, re-evaluation of the history of British topographical art will see Graham take his place alongside the best this country has ever produced.