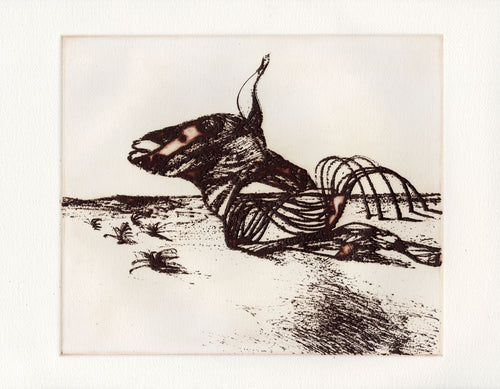

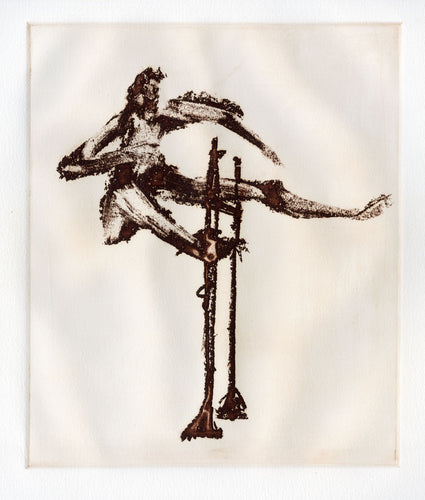

Horse – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

But before any European stepped foot on its shores, Australia had long lived a double life of its own. This is among the oldest, largest, flattest, and driest masses of land in the world. A home of extraordinary life and wealth: a hotbox of evolutionary weirdness, teeming with floral and faunal idiosyncrasies – and, in places, a natural cemetery, its biodiversity matched only by its capacity to kill. Australia was not impressed by the arrival of the white man, and summarily dispatched him with various extremes of season, weather, and venomous beast. Those it did not starve by crop failure, finish by flashfire, wither by poison, exhaustion or thirst, it whittled by killing off what little livestock was reared in those early years of settlement.

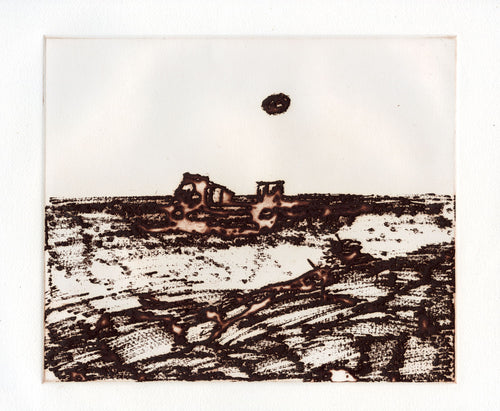

Carcase III – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

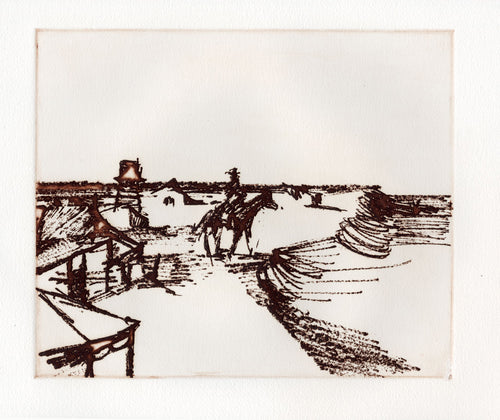

Sidney Nolan painted many versions of Australia: by air, up creek, small town and desert dune, but it is a slow, murderous homeland that provides the setting of Dust, a suite of 25 etchings published in 1971 after earlier drawings made in the winter of 1954 in London. The originals were in part inspired by Nolan’s time with the film crew of John Heyer’s The Back of Beyond, the wonderful 1952 docu-drama of one legendary mailman’s journey along the Birdsville Track, a three-hundred-mile stretch of stock train road from the tiny eponymous whistle-stop, through the depths of the Australian outback, to the little town of Maree. He met the crew on a travelogue commission from Brisbane’s Courier Mail to document the catastrophic drought then gripping much of rural Queensland and the Northern Territory.

Birdsville Hotel; from Nolan 'Drought' photographs, 1952

Untitled (Camp Bed), 1952

This is desolate country; much of it empty of people and rich in folklore, tyrannical in its unbroken flatness, with nary bush nor bosk thick enough to mask the oppression of the midday sun. The experience burned itself into Nolan’s memory and on his camera film, and in Dust, more than a decade later, he looked to recapture its power in the bite of the etcher’s acid: ‘There is quite a trench...I forget just how deep it was, but more than a thirty-second of an inch. It’s quite deep, so that when the ink is rolled on – or in – it comes out very embossed. You can run your fingers over it and feel a distinct bump. It looks the opposite of the scrape-method I use to get transparency; the shimmering light in the centre of Australia...but you still get something of the same interpenetration of light.’

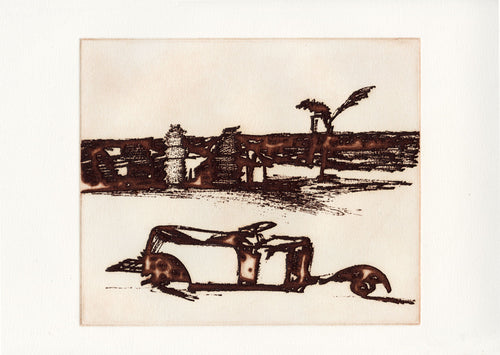

Carcase II – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

Along the trail Nolan encountered dead cattle and horses shrivelled in the sun, their bodies littered across the savannah in a catalogue of inexplicable postures: upended, flattened like canvas and petrified mid-step. Some, the drowned victims of last year’s seasonal monsoons, were now found perversely suspended from trees after the evaporation of the bogland water. Many had died not from the heat, but during the freezing nights, only to be discovered still huddled in the morning, where they were left to bake. Jackaroos – young stockmen – were unable to transport herds for agistment elsewhere; railroad connections then were rudimentary, and the area affected covered virtually every breeding ground of the Australian cattle industry. Paralysed with indecision whether to bring water to the cows or the cows to water (what water could be found), a million and a quarter animals perished over the duration of the drought, more than a fifth of them stranded needlessly along stock routes.

Untitled (Calf Carcase in Tree), 1952

Cow Carcase and Skull, 1952

Greatly affected by what he found, Nolan took over 60 photographs of these mummifying corpses, ‘strewn on the baked and cracked plains.’ As it had done to weekly reporters on the disaster, it seemed to him an event of almost providential significance: ‘There is a brooding air of almost Biblical intensity over millions of acres which bear no trace of surface waters. The dry astringent air extracts every drop of moisture from the grass, leaving it so brittle that it breaks under foot with the tinkling of thin glass.’

Untitled (Brian the Stockman Mounting Dead Horse), 1952

Untitled (Desiccated Horse Carcase Sitting Up), 1952

Such conditions have long favoured wilier survivalists. Australia’s native monitors, its corvids, its dingoes, are all scavengers; their adaptation to its harsher climes, and their persistence through drought and desiccation, succeeding like bushrangers on the failures of others, have made a long and cruel mockery of attempts to turn Australian savannah land, some of it the least fertile in the world, into sites for rearing cattle. In a print titled Mulka, after a cattle ‘station’ or reservation off the Birdsville Track, Nolan gives us a tree top that could be mistaken for the wing-sweep of a buzzard or crow; the rusty frame of an abandoned plough or camp bed its carrion.

Mulka – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

Returning to the source material of photographs and drawings twenty years on, the parallels between the phenomenon and the etching process felt inescapable: the ‘heat’ of the acid – now chemical, not solar – sears the surface of the plate, dissolves and digs into it and fossilises its image in metal, much as the drought had left its cracks in the earth. As the name Dust would have us know, this is a series about death: a lifeless landscape where living things are returned, ‘ashes to ashes’, to the hard earth. Horns and bones, plucked clean of meat, stick up out of the dirt like ossified landmarks, like dead trees, like skull-and-cross-bone signposts in scrubland. In places the bite is so deep, the etching ‘trench’ so broad, it as if the acid had burned through the plate onto the page and the print were now bleeding out before you, like a photograph peeling in the fire: a corrosive warping, leaching, smearing, grimacing.

Carcase – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

There is a strange and eerie openness to the landscape of Dust, which to foreign eyes might appear imaginary; a Surrealist scantiness, like those grand sandbox arenas of de Chirico, Dali and Magritte, but in fact anyone who has flown by plane over Central (known colloquially as ‘Empty’) Australia, as Nolan did in the late 1940s, or who has ridden out into the desert by truck, or has seen some of the extraordinary photographs he took, will know that this is a more or less realistic depiction of the boneyards the outback becomes in high summer. It is a setting which is decidedly lunar; which television scientists have, in recent years, used to make more real to us the waterless landscapes of Mars or the Moon.

Township – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

Architecture – man’s ultimate imposition – stands ridiculous in this terrain: colonial-era townships and soapbox verandas with all the permanence of a cereal packet. Their scrappiness serves to remind us of the politics of this place; the history of the formerly dispossessed striving, in these least habitable reaches, to carve their own niche, much like those entrepreneurial rangers who crossed the mid-west of America to stake a claim, only to be met with the vicious realities of frontier affray: indigenous genocide, the hardened cull or be killed mentality with which America is still desperately trying to come to terms even to this day.

Bewildered by the hugeness, the vast apathy of the land before them, frontiersmen arriving in the Wild West struggled fiercely to impose some sense of European manners on an utterly uncaring wilderness, with fatal consequences for the ‘primitive’ natives they found already living there. Their passage was adopted in later years as the defining moment of America’s foundation myth; its settlers, cowboys, and sheriffs enshrined in legend as its first celebrities. But in Australia, there was only one major equivalent figure: Ned Kelly, a name so synonymous with Nolan’s that you cannot think of one without the image of the other.

Ned Kelly – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

Artist and bushranger shared an immigrant heritage: Kelly, the son of a pig-rustler father and a migrant – that is to say, not criminal – mother, both of Irish stock. Part brawler, part poet manqué, today he would probably be described as a ‘delinquent youth’, born in the same month as the notorious Eureka Stockade incident, in which prospecting miners rebelled against administrators’ efforts to quash ‘illegal’ mining on Crown land at the height of the Victorian gold rush. In this turbulent social context, the young Kelly soon took to crime. While under the employ of senior bushranger Harry Power he was arrested several times by police and brought before magistrates for counts of rustling and pilfery, much of which he certainly committed, much he patently did not; an injustice that quickly instilled in him a hatred of authority figures.

After serving a hard labour sentence for two years, Kelly returned to rustling until 1878, when a fracas with a constable at the Kelly household saw his mother arrested for attempted murder and a like charge brought against Ned and his brother, Dan, neither of whom were likely there. In retaliation, the infamous Kelly gang foursome was formed; embarking on bank robberies, station raids, hotel hostages, and brutal confrontations with police and informants, they racked up sizable bounties over a two-year period. In a move that highlighted the social inequities of which the Kelly episode became the paradigm, the police even employed black aboriginal trackers (with the promise of rewards which they never received) to help root out the Irish Kelly gang. Eventually, the Kellys were subdued during a prolonged showdown at a Glenrowan hotel: two of the four were shot dead, and Kelly (riddled, the story goes, with 28 bullet holes in his body) was dragged before the authorities. When the judge – the same who had sentenced his mother – completed his sentencing with the customary ‘May God have mercy upon your soul’, Kelly is supposed to have replied, ‘I will go a little further than that, and say I will see you there where I go.’ He was hanged at 25 and a half – and within 8 months the judge followed him to his grave.

Kelly – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

Thug, begrudging bandit, or revolutionary martyr, Kelly’s place in Australian history is still in dispute. But just as you cannot think of Nolan without Kelly, Nolan could not conceive of an Australia without its most famous underdog; and so he reappears here in Dust with reassuring inevitability, somewhere between phantom and cardboard effigy, conjured from the country’s past and propped up among this barren landscape, his spirit to inhabit forever the brush of ‘Kelly country’.

Heroism and defiance, in both the indigenous population and the European exiles who settled here, defines Nolan’s Australia. The legend of Kelly lies at the heart of that strain of his art, but he drew on native myth too. The Wandjina petroglyphs in Kimberley, Western Australia, are among the earliest aboriginal murals to have survived their 4000-year history. Made with red, yellow and black pigment on white ground, these images of celestial creators were repainted continually to ensure their persistence and power, and to herald, or to encourage, the coming monsoon rains. There are conscious parallels with these paintings in Dust: the etching plate as a hard, talismanic medium, the layered and layered painting mirrored in the continual re-inking of an edition. But Nolan’s equivalents portend no such deluge; they are not mythological dreams of reverence but a scorched record of persistence, one often futile, in the face of environmental and ecological heat death.

Jinker – Sidney Nolan, 'Dust'

For one so invested in myth and mythicism, dread realism is the decisive thrust of Dust. The heroism of Kelly flounders in the upfront bathos of the country, a mean indifference that even his spectre cannot outdo. Looking back on the drought and carcass paintings and the photographs which inspired them, Nolan was reminded of seeing the calcified remains of the victims of Pompeii: ‘I feel that maybe this is the fate that awaits Europe.’

Untitled (Cow and Calf Carcase Covered in Dirt I), 1952

What, then, would he make of the fires raging across Australia today? A tenth of New South Wales national parks under bushfire, a fifth of the Blue Mountains aflame, 2 million hectares burnt in 6 months? Would we have paintings of a new Australia, in the grips of a very 21st century crisis: smoke blankets over Sydney, or the citizens who dragged the charred remains of their houses to protest at the foot of Canberra’s Parliament House – carcasses of a new and chilling kind.

Or might he point us to Dust, and to the photographs before it, to say ‘we have been here before; I have shown you already’ – and, perhaps, finding an indifference not of climate but of human corporations to blame, invoke Kelly one more time: ‘I will see you there where I go.’