In anticipation of our upcoming exhibition marking Jim Malone's 40 years as a studio potter, we thought we'd offer our readers a workshop tour of Malone's Cumbrian pottery for this week's Making post.

With the first batch of exhibition pots delivered in the last two weeks, preparations are well under way to make this ceramics show a special event to celebrate such a huge achievement. The work is looking beautiful, with pots starting to appear on our website, so read on for a sneak peak into the amazing working life that has seen their production.

Tucked away into the North-West corner of Cumbria along the banks of the River Waver lies Lessonhall, a small, remote village where, 13 years ago, Jim Malone established his current pottery studio.

Just north of the Lake District, this is wild country, with boglands and moorlands, lowland valleys, dark peaks and fells and rolling black clouds. A place of great natural beauty, this area has inspired generations of writers and artists, drawing the likes of Wordsworth, Ruskin, and Tennyson to its dramatic panoramas.

Malone's house and workshop are situated in the midst of the village, nestled away from the main road between local farmhouses and surrounding cottages. Quiet and unassuming, the building hides a lush, green garden from view, blooming with vegetable beds, climbing roses, and a moss-carpeted wall.

As is often the case with our gallery potters, Malone is a self-sustaining man. In addition to his craft, he and his wife have cultivated a tiny garden of paradise, complete with raised beds of tall, proud onions, broad beans in abundance, sprawling courgette plants, and young fruit trees weighed down with their bounty.

Set amongst this world of growth, Malone's pots seem part of a wider lifestyle built around care and contemplation - not merely the product of occupation, but the nurtured fruits of a labour that has become a way of life.

This is a slow pace of life, of which this space has become a major part. Feeding physically with homegrown vegetables and spiritually with seasonal flowers, Malone's garden becomes an analogy for his work as a potter: meditative, involving respect for one's natural materials, working with nature to produce something that is not pretentious or overthought, but carefully planned and made for use and enjoyment.

Indoors, Malone's house is home to all manner of beautiful functional pottery, both his own and works by contemporaries such as Svend Bayer and Mike Dodd, alongside whom Malone taught whilst at Cumbria College of Art.

Hand-thrown jugs welcome flowers, bowls receive fruit and vegetables, making a union between the labours of the garden and those of the wheel and kiln.

Malone's work draws on a number of influences, many of which first inspired the likes of Hamada, Leach, and Cardew in the 1920s, '30s and beyond.

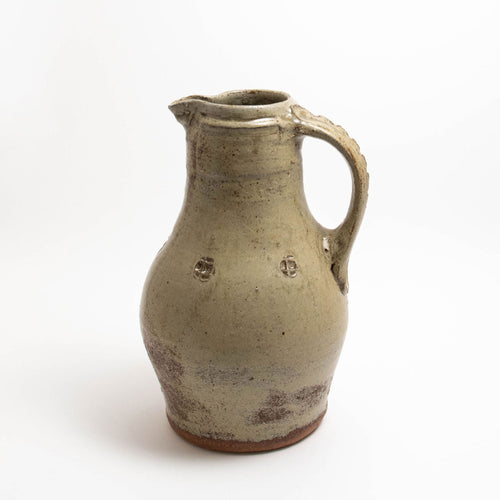

Forms are derived in particular from the work of 14th century English and 16th century Korean potters: mediaeval-style jugs, Korean bottles, and especially Hakeme - the Japanese term for this Korean technique - a type of decoration that involves brushing white or cream slip over a darker clay body beneath, frequently (in Malone's hands at least) adorned with further iron brushwork depicting rushes, wheat sheaves, and leaping fish.

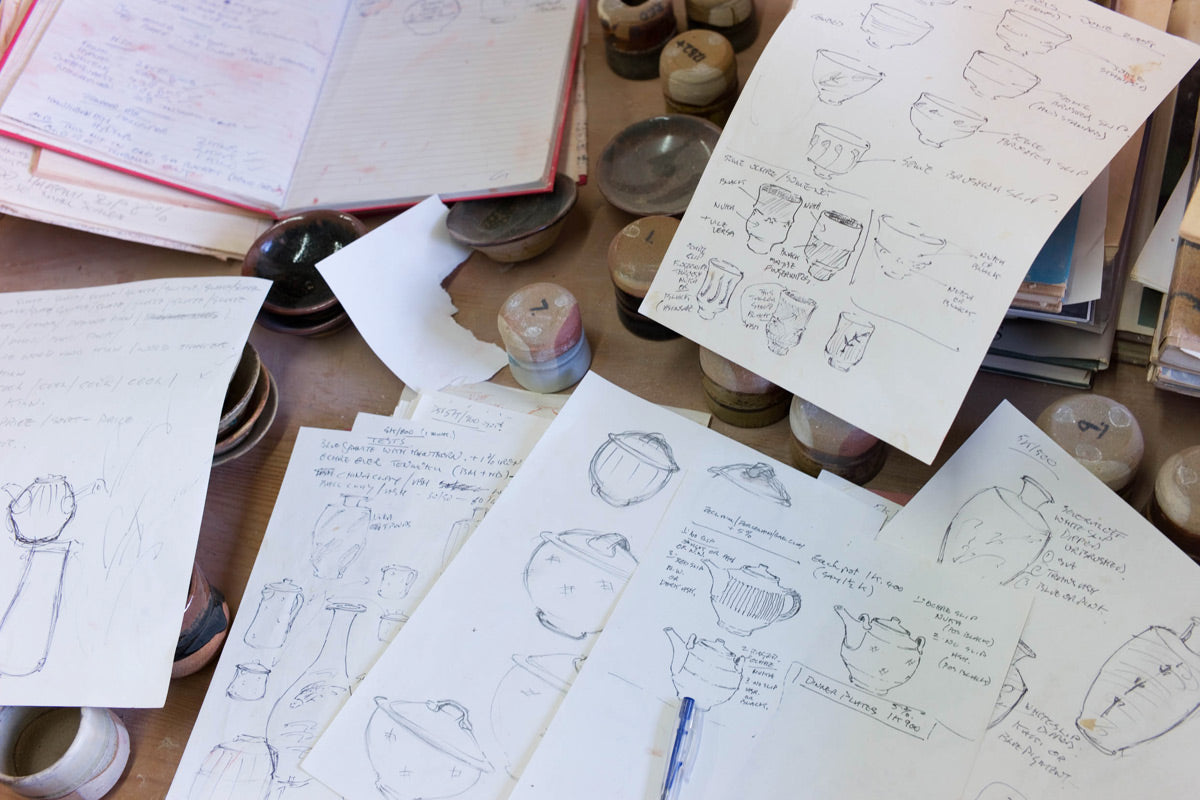

Littered throughout the house are sketches and designs made ahead of throwing, Malone noting the forms he wishes to make and the glazes and decoration that will be applied to them in the weeks ahead.

Throwing sessions can last anywhere between six weeks and two months, Malone drawing upon his invaluable student experience as a production potter under Ray Finch at the legendary Winchcombe Pottery to aid what is often a lengthy and draining task.

Malone throws upon a hand-built momentum kick-wheel, eschewing what he sees as the relentless drive of an electric wheel for something with a less regular rhythm. The resulting rotational motion has a kind of pulse that Malone finds almost hypnotic, and which dictates the throwing process as much as the movement of hands, fingers and thumbs.

Once thrown and glazed, pots are often decorated with brushwork, iron and cobalt-rich clay pigments being applied with traditional brushes in relaxed, generous sweeps.

Thrown, decorated and stamped, Malone's pots are then fired in his kiln, housed in an adjacent building. A two-chambered, oriental-style climbing kiln, it is fired with a combination of oil and wood: certain glazes can be spoilt by too much ash, and the introduction of oil lends greater control over chamber draft and temperatures and the amount of fly-ash deposited on Malone's pots.

He describes how the irregular pull of air through each chamber gives the kiln a living breath, a heartbeat that is palpable during peak temperatures and which transforms the kiln into a slumbering beast, slowly awoken from its sleep during each firing.

Pots ready for firing are stacked on nearby shelves, patiently waiting for the kiln packing. They will be placed next to one another carefully and consciously in an attempt to predict the distribution of ash and heat throughout the two chambers.

The results of Malone's hard work, his hard-earned knowledge of kiln temperament, glaze behaviours, and skilled throwing, speak for themselves.>

His Tenmoku glazes, deep, rich and black, break to soft warm oranges and rusty browns; his hakeme, lusciously applied to bottles and bowls, appears effortless; each ash pool, wax resist motif, hand-pulled handle, and faceted side reiterate their maker's expertise, hard-won over four decades of successfully managing studio workshops.

At 70 years old, Malone is rightly thought to be among the country's top living potters, a bastion of the Anglo-Oriental school and a maker of slow, quiet, enduring work in a world in which the fast and fashionable so often takes the limelight.