Etruscan Reunion

Born in London in 1931, Thornton’s early childhood was interrupted by the advent of the Second World War. Forced to evacuate to Montreal with her two brothers, she returned to England in 1944 as a young teenager with a burgeoning interest in the world of art. Early technical education came by way of the Byam Shaw School of Drawing and Painting, followed by the Regent Street Polytechnic where she studied under the careful watch of Pat Millard.

Millard, whose students included the multi-talented Michael Ayrton and John Minton, instilled in his pupils a profound appreciation for the works of the English Romantics, William Blake and Samuel Palmer. Tutorial discussions were open and experimentation was actively encouraged, almost to a fault: fellow undergraduates recall being left to their own devices until finding themselves in a ‘helpless mess’ before Millard would intervene and point them in the right direction.

Escó, Sigues, Spain

This was a critical period of discovery. Thornton’s naturally investigative temperament saw her studying the Neo-Romanticism of Graham Sutherland alongside the abstract landscapes of the St Ives group. For her twenty-first birthday she was gifted an oil painting by Winifred Nicholson, a fellow Byam Shaw alumna known for her impressionistic window views that combine still life compositions with alluring panoramas. Nicholson would become a profound influence and, in later years, a close friend after inviting Thornton to visit her Cumbrian home.

Tower of London

Perhaps most important of all, it was during these early formative years that Thornton first established her love of architecture after witnessing an exhibition of church photographs. In her own work she would bring this expansive mélange of influences to bear, enlivening her illustrations of cathedral galleries and church doors with an intuitive sense of texture and surface developed in these early years of study.

Sanguesa

If London had offered new avenues of inspiration, it was in Paris, enrolled on an eight-month residency with Stanley William Hayter at the renowned Atelier 17, that Thornton received the fundamental practical experience that launched her career as an etcher. Founded some thirty years earlier, Hayter’s workshop had gained a reputation for its extraordinary advances in the etching process, revolutionising the way that artists could manipulate colour and tone in a medium otherwise characterised by a preponderance of shades of black, brown and grey. Past collaborators included modern art’s giants, from Picasso to Miró, and amid the vapoured fumes of acid and ink the studio atmosphere was one of endless possibilities.

For Thornton, the apprenticeship was ‘electrifying’: of particular interest were Hayter’s experiments with ink viscosities, which allowed multiple colours to be applied simultaneously and printed from the same plate, and an audacious use of the acid bath, in which plates were unevenly submerged and the bite of the acid manipulated to create a diverse spectrum of surface effects.

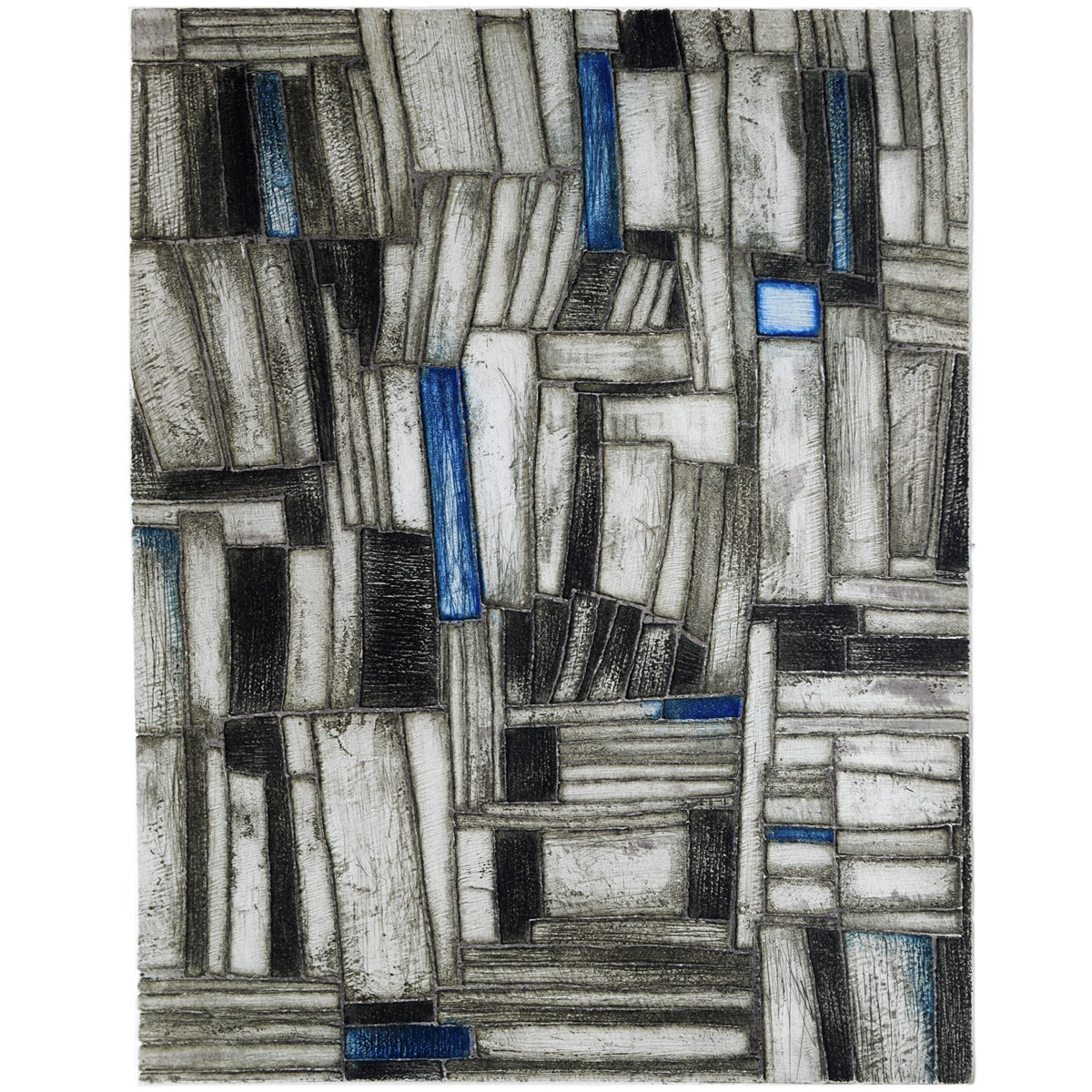

Blue Slate Stone

Thornton emerged from her placement a changed artist. Returning to England in 1954, she sought out her own etching equipment and quickly set up her own miniature studio. The following two decades were filled with extensive travel, from Italy, Spain, and France to a further residency at the Pratt Institute in New York and a funded research trip to Mexico.

St Amànd de Coly

Though the native architectural practices of each new destination provided fresh examples of visual interest, 11th and 12th century Romanesque architecture was an inspirational mainstay. Typified by high-vaulting ‘Roman’ arches, its curvilinear arcades, cavernous halls, massive rising columns and geometrically carved ornamentation offered a wealth of angles, lines, shadows, and surface qualities to translate into the ground of the plate.

San Miniato

Historically, topographical etching has been the medium of perpetuity. Artists like Giovanni-Battista Piranesi sought to record for posterity the great architectural achievements of civilisations with a sense of monumentalism, or in their fantastical capriccii to invent gargantuan, intertwining structures that defy all reason. In Thornton’s hands, the genre is subverted; far from presenting an authoritative record of place, she conveys a sense of the organic life of these buildings, stressing the impact of weather and the passage of time. Churches are lent mottled, marbled textures as the effects of the etcher’s acid mimic the corrosive forces of rain and frost on pockmarked walls.

detail from San Pedro de la Rua

In ‘San Pedro de la Rua’, Thornton’s view of the arched doorway and the cascading steps beneath combines rich surfaces with a depth of perspective that leads the eye vertically up through the composition. Abstract shapes, like the echoing, semi-circular vaults of Casserres, reinforce the often colossal scale of this period of architecture, but in her expert use of texture we are reminded always of impermanence; of the constant erosion that will eventually topple these towering constructions.

Casserres

When challenged on the lack of figurative elements in her work – people and animals seem seldom to appear in her prints – Thornton rebutted that it was the stone that was her living subject. Her etchings of church pillars and priories, pitted walls and crumbling friezes are a textural tour de force, standing toe-to-toe with contemporary efforts by the likes of Julian Trevelyan or Norman Stevens in their technical invention and ingenuity.

As a founding member of the Printmakers’ Council and fellow of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers, she was highly regarded by her colleagues; but as a female artist specialising in an outmoded medium, her quiet, contemplative body of work has been unduly neglected. Like the mutable structures she so beautifully etched, with time, one hopes, that will change.