Michael Rothenstein (1908-93) was perhaps the most experimental British graphic artist of the 20th century.

The son of Sir William Rothenstein, the illustrious painter, printmaker, portraitist, and Principal of the Royal College of Art, Rothenstein began life surrounded by art. From an early age he was encouraged in his own studies, eventually enrolling at the Chelsea School of Art in 1923.

Untitled (Purple, Red and Green) - a typically colourful Rothenstein print, produced from a combination of woodcut and linocut blocks

Untitled (Purple, Red and Green) - a typically colourful Rothenstein print, produced from a combination of woodcut and linocut blocks

Despite his obvious talents in the landscape watercolours and drawings he produced throughout the 1920s, the combination of a rare and encumbering glandular illness that stayed with him until 1940 and debilitating depression meant that Rothenstein exhibited very little in his early career and his stylistic development came slowly.

three cockerel prints: Cock's Head (above left); Julie Christie (above right); and Two Cockerels II (below)

three cockerel prints: Cock's Head (above left); Julie Christie (above right); and Two Cockerels II (below)

After a first one-man show at the Redfern Gallery in 1942, the many diverse processes of printmaking began to attract Rothenstein towards graphic work. In 1946, with his first editioned print – Timber Felling in Essex, produced for the School Prints initiative - he decided to venture fully into the world of the printmaking. After a flurry of experimental works produced with the help of outside printers, in 1954 Rothenstein established his own studio in Great Bardfield where he began to produce from his own presses.

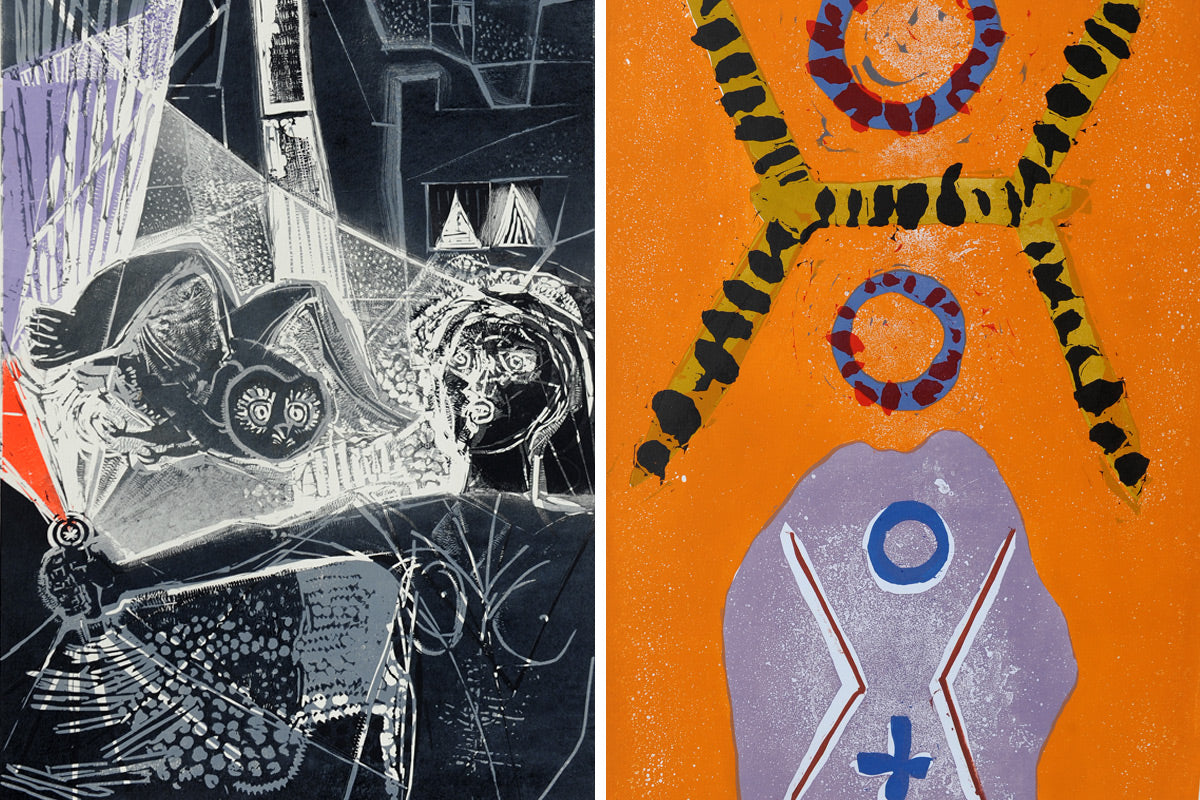

experimentations in photo-screenprinting (above left); woodcut and linocut (above right); and etching (below)

experimentations in photo-screenprinting (above left); woodcut and linocut (above right); and etching (below)

Working with a childlike curiosity, he tried his hand at every printing method available to him. His fascination led to a myriad of new techniques which he developed on as many different media: driftwood and sheets of iron, scrubbed with sandpaper or ground with power tools, became printing blocks whilst metal scraps, photographs and other refuse were incorporated into the process.

She's American (woodcut and photo-screenprint, above); below, Michael Rothenstein working in his atelier and one of his huge, mixed media printing blocks making use of wood's natural grain

She's American (woodcut and photo-screenprint, above); below, Michael Rothenstein working in his atelier and one of his huge, mixed media printing blocks making use of wood's natural grain

Over the next four decades Rothenstein ceaselessly dedicated his time to printmaking, at the almost total expense of his work in other media. In 1967 he moved to Stisted, Essex and new workshop premises with the Argus Studio, where he worked alongside several printers who aided with the printing of his more complicated blocks and plates. His imagery in these prints straddled a divide between figurative portraits and depictions of animals, especially the cockerel, and abstract combinations of form, colour and texture.

Rothenstein was introduced to linocutting, the method employed in The Torch (above left) and Orange and Violet (above right), by fellow printmaker Edward Bawden; below, an untitled woodcut

Rothenstein was introduced to linocutting, the method employed in The Torch (above left) and Orange and Violet (above right), by fellow printmaker Edward Bawden; below, an untitled woodcut

So relentless was his drive and energy that it seemed Rothenstein was making up for those lost years in the 1920s and ‘30s. As well as pulling countless new editions from his eagle-crested Columbian press, Rothenstein also lectured extensively on his techniques and produced several publications, travelling frequently to talk to audiences about the importance of the print as a medium in its own right, and not merely a tool for reproduction.

Mike Goldmark and gallery members Kate and Marc look through the work in Rothenstein's estate; also above, Rothenstein's enormous Columbian Press, which now resides in the Goldmark Atelier; below, Figure and Yellow

Mike Goldmark and gallery members Kate and Marc look through the work in Rothenstein's estate; also above, Rothenstein's enormous Columbian Press, which now resides in the Goldmark Atelier; below, Figure and Yellow

His philosophy was that each print form need not to be treated as if it were a separate practice:

My feeling is that each technique in printmaking is like a single instrument producing its own range of sound but that these instruments need not always be played separately as they have been in the past. We live in an age when transformation between techniques is made available through phototechnology and in this way the single instrument is less separate – it is capable of merging, of being used in concert – of producing a symphony, with a new kind of orchestration.

Rothenstein's woodblocks, blackened with ink; below, a bold hand-coloured woodcut of Fredrikstad Fair

Rothenstein's woodblocks, blackened with ink; below, a bold hand-coloured woodcut of Fredrikstad Fair

A figurehead at the very forefront of the 20th century British printmaking renaissance, Rothenstein died at his home in Essex in 1993. His prints embody the same excitement and daring that galvanised their production: rich in colour and spectacularly textured, they represent an artist exploding the boundaries of traditional printmaking.